When a Rope-a-Dope Strategy Makes Sense

Companies usually retaliate against competitive attacks. But sometimes the best strategy is to hold back.

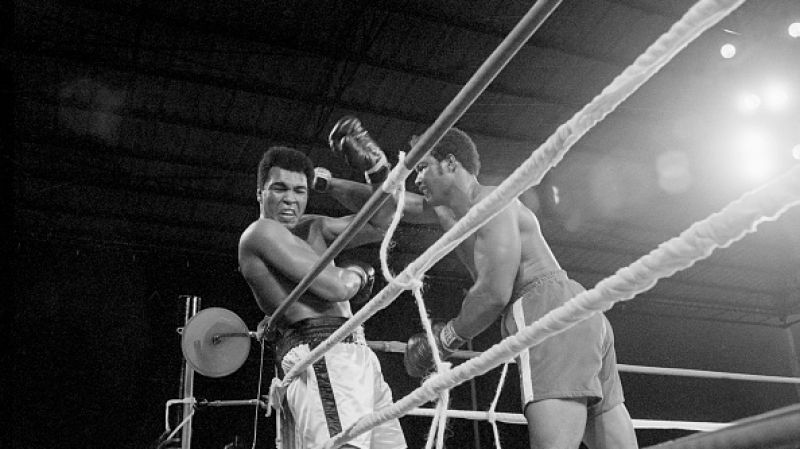

In The Art of War, the ancient military classic, Sun Tzu had advice for those who would rush to battle. He pointed out that it is equally important for warriors to know when not to fight as when to fight. In 1974, Muhammed Ali took this insight to heart when he used the rope-a-dope strategy during a boxing match. Ali spent the early rounds of the bout leaning back on the ropes and letting his opponent, George Foreman, deliver punch after punch. By the eighth round, Foreman was a spent force and could not defend against Ali’s decisive blows.

Strangely, we do not hear much about Sun Tzu’s advice in executive offices. There, the focus seems to be on the first part, when to counterattack, and little on the second part, when to hold back. The expectation is that a competitive action requires an immediate response. The main questions at that point seem to be: Should the response be proportional, equivalent or greater than the attack? If we’re attacked in this market, do we respond in the same market or open a new front? And do we counterattack with, say, matching price cuts or a promotional campaign?

Sometimes, though, managers decide to do nothing. They strategically forbear from responding to a rival. They are aware of the attack and have the resources to respond but see the benefit of standing down. This is not a failure to act. This is not a sign of weakness. This is the ability to avoid being lost in the moment.

From psychology, we know that when people feel threatened, they narrow their attention to the immediate situation. They focus on the attacker or the attack and the immediate outcomes. That impulsive behaviour is why some firms counterattack even though they can end up losing down the road.

But some executives do not give in to impulse. They see beyond the attack and immediate outcomes and instead focus on long-term consequences. Psychologists call this transcendence–the ability to focus awareness beyond the immediate stimulus.

The art of transcendent thinking

In research I conducted on strategic forbearance with Danny Miller of HEC Montréal, we identified three forms of transcendent thinking in competitive situations: spatial, temporal and systemic.

Spatial transcendence involves focusing beyond the attacker. A transcendent thinker takes into account a broader set of stakeholders: other rivals and their alliance partners, customers, shareholders, suppliers and regulators. Does the attacker, for example, have allies that are powerful? If so, and a firm gets into a competitive war, they may face the attacker’s ally or other rivals as well. Yet another actor is government: a firm with a dominant market position may not want to attract regulator interest by counterattacking if doing so causes turmoil in the industry.

A firm may also want to avoid getting into a war that undermines customer expectations. Product quality was a concern when McDonald’s chose not to respond to Burger King’s introduction of french fries with 30 per cent fewer calories. Even though McDonald’s had the firepower to respond in kind to Burger King, it did not want to risk aggravating its customers.

The second type of transcendence is temporal. Some firms look beyond the duration of an attack to consider past and future competitive interactions. Familiarity between rivals leads to the development of norms for less aggressive competition. In this sense, forbearance is a tool for preserving non-confrontational relationships. It can also restore and maintain alliances with competitors, thus reaping benefits from past investments in collaborative projects.

As with the past, so too with the future. When a firm that has been attacked envisions continuous competitive interactions in years ahead, forbearance makes sense. Expected future returns outweigh any short-term gains of counteraction. There are always other ways to respond than going directly against a competitor.

Counterattack or stick with the plan?

The third type of transcendence is systemic. This involves assessing how well a potential counterattack fits with the overall corporate strategy, rather than assessing its immediate effects. A competitive response, for example, could prevent a loss of market share in the short term but knock a firm off its long-term strategic path. In addition, forbearance can preserve resources to pursue other strategic options that are consistent with the firm’s larger strategy.

A classic example comes from the airline industry. American Airlines, Delta Air Lines and United Airlines all introduced no-frills basic economy in response to competitive pressure from low-cost carriers. By contrast, Southwest Airlines decided it would not follow that path because, in the words of its CEO, “that’s not what we do.” He added, “We have, we think, better opportunities that fit our brand.”

Rejecting the option to counterattack can also provide time to learn the impact of rival actions and observe how others respond. A case in point is Airbus’s decision not to respond to Boeing’s new mid-market airplane concept in order to buy time and assess market reaction.

Transcendence in strategic planning

You can easily use strategic forbearance when calibrating competitive responses. The standard Awareness-Motivation-Capability (AMC) framework can be extended to incorporate transcendent thinking.

In analyzing whether to counterattack, first consider awareness:

-

Are there competitive moves that you’re overlooking?

-

Does overexposure in one market make you vulnerable in others?

-

Do you have enough bench strength in competitive intelligence to predict where and when attacks will be launched?

If you’re aware of a competitive threat, the next questions are:

-

Do you have the capability to respond?

-

If not, how soon can it be developed?

If it is impossible to develop, your counterattack is a moot point. If you have the capability, however, it does not mean you should hit back right away.

At this point of analysis, transcendence comes to the fore. First, spatial transcendence: If we respond, will other rivals enter the fight, putting us in an even worse position? Does my rival have another ally that I do not want to confront? Are there other stakeholders that need to be considered?

Temporal transcendence: If I counterattack, will I jeopardize a co-operative relationship with my rival? Do we expect many competitive interactions in the future?

Systemic transcendence: Will a counterattack conflict with our overall strategy and strategic positioning? Does a counterattack prevent us from pursuing other strategic options?

Choose forbearance when your analysis suggests that its benefits exceed short-term losses. If you determine from your answers that a competitive counterattack makes sense, you then move to a new set of considerations: What should be the magnitude, timing, domain and type of response? Similar analysis can be applied to predict a rival’s incentives to forbear.

We encourage executives to go beyond a single attacker, attack and immediate outcome when considering competitive responses. Mindful managers can transcend the urge to retaliate by considering how a potential counterattack could shape future behaviour of rivals, allies and stakeholders. By doing so, they can assess the long-term, systemic fruits of forbearance. The benefits can be substantial: de-escalating competition, maintaining strategic flexibility, preserving collaborative ties with partners, aligning with stakeholders’ expectations, improving strategic coherence and pacing transformation and adaptation. Transcendent thinking can be critical for keeping these benefits in mind.

Goce Andrevski is an associate professor and Distinguished Faculty Fellow of Strategy at Smith School of Business, Queen’s University.