Lightweight Digital Tech Can Do Heavy Lifting When Disaster Strikes

Social media, mobile apps, analytics and cloud computing prove their worth at each phase of a pandemic response

Amid the horrific public health and economic fallout from a fast-moving pandemic, a more positive phenomenon is playing out: COVID-19 has provided opportunities to businesses, universities, and communities to become hothouses of innovation.

Around the world, emerging digital technologies are driving high-impact interventions. Artificial intelligence helps identify individuals with suspected COVID-19 symptoms. Drones conduct area surveillance and handle logistics safely. Telemedicine enables consultations to be offered remotely. Equipment based on the internet of things instantly alert hospital staff to errors or new requirements. Just a few years ago, some of these applications would have been seen as the stuff of science fiction.

As impressive as these applications are, what we find striking is the outsized impact of more modest, readily available digital technologies (RADTs). In the midst of a maelstrom, these technologies—among them social media, mobile apps, analytics and cloud computing—help communities cope with the pandemic and learn crucial lessons. Community and public health leaders are handling time-sensitive tasks and are meeting pressing needs without having to possess much technical knowledge.

Digital technology showed flashes of potential in the early 2000s. At that time, Singapore managed its SARS outbreak by investing heavily in IT infrastructure to streamline communications, manage cases and handle contact tracing. In 2011, social media emerged as powerful disaster response platforms during cataclysmic flooding in Thailand. Similarly, ham radio communications and low-tech solutions have been leveraged by communities with damaged public infrastructure during hurricanes in the southern U.S. and other natural calamities in developing countries such as Thailand.

Crisis management

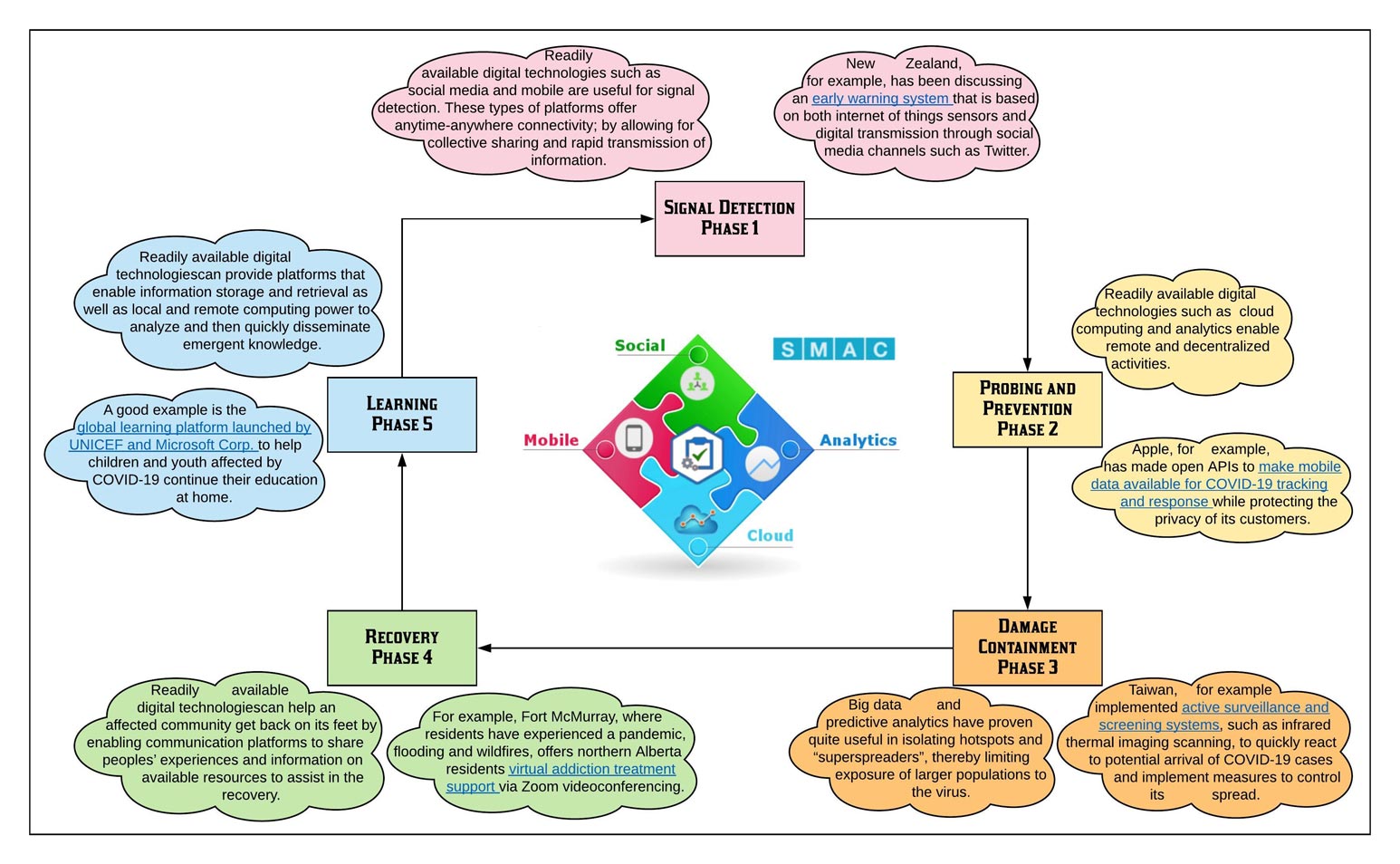

To gauge how this potential is playing out, our research team looked more deeply at how communities are incorporating RADTs in their responses to disasters. As a starting point, we used an existing model of crisis management, developed in 1988 by organizational theorist Ian Mitroff. The model has five phases: signal detection to identify warning signs; probing and prevention to actively search and reduce risk factors; damage containment to limit its spread; recovery to normal operations; and learning to glean actionable insights that can be applied to the next incident.

The 5 phases of crisis management

Although this model was developed for organizations dealing with crises, it is easily applicable to communities under duress and has been used to analyze organizational responses to the current pandemic.

Our research showed that digital technology can be deployed during each phase of a crisis, offering a variety of capabilities.

Phase 1: Signal detection

Being able to identify potential threats from rivers of data is no easy task. RADTs such as social media and mobile are useful for signal detection; they offer anytime-anywhere connectivity and allow for collective sharing and rapid transmission of information. New Zealand, for example, has been discussing an early warning system that is based on both internet-of-things sensors and digital transmission through social media channels such as Twitter.

Phase 2: Prevention and preparation

RADTs such as cloud computing and analytics enable remote and decentralized activities, a more flexible alternative to site-specific information systems. Digital technology that supports this phase ranges from volunteer co-ordination portals to training and simulation services that heighten the level of community preparedness. Apple, for example, has made open APIs to make mobile data available for COVID-19 tracking and response while protecting the privacy of its customers.

Phase 3: Containment

Not all crises can be averted. But almost all crises can be contained. Big data and predictive analytics have proven useful in isolating hot spots and “superspreaders”, thereby limiting exposure of larger populations to the virus. Taiwan implemented active surveillance and screening systems, such as infrared thermal imaging scanning, to quickly react to the potential arrival of COVID-19 cases and implement measures to control its spread.

Phase 4: Recovery

Previous research has emphasized social capital, personal and community networks and a shared experience of post-crisis sense-making as essential factors for the recovery process. RADTs can help an affected community get back on its feet by enabling communication platforms to share peoples’ experiences and information on available resources. For example, Fort McMurray, where residents have experienced a pandemic, flood and wildfires, offers northern Alberta residents virtual addiction treatment support via Zoom videoconferencing.

During recovery, it is also important to foster a sense of equity to avoid only certain community members receiving preferential services. To address this need, anti-hoarding apps for personal protective equipment and apps that promote volunteerism and social bonding could prove useful.

Phase 5: Learning

The most valuable learning processes aggregate knowledge from multiple sources and help community members collectively make sense of what they experienced. Readily available digital technologies can provide platforms that enable information storage and retrieval as well as local and remote computing power to analyze and then quickly disseminate emergent knowledge. A good example is the global learning platform launched by UNICEF and Microsoft Corp. to help children and youth affected by COVID-19 to continue their education at home.

The resilience phase

From our research findings, we propose a sixth phase of crisis management: community resilience. Communities need to develop the capacity to absorb the impact of pandemics or other disasters that seem to be arriving at their doorstep with greater frequency.

RADTs play a key role here as they provide the technical and organizational infrastructure to convert tacit knowledge of overcoming disasters and crises into explicit knowledge that can be stored, retrieved, analyzed and shared.

Especially during a pandemic (when face-to-face interactions are limited), these technologies can enable community participation through social media groups, virtual meeting software and cloud- and mobile-driven engagement and decision-making platforms.

Digital technologies that provide transparent information services such as analytics-based, data-driven dashboards and real-time updates are especially useful in creating a sense of equity and caring. Apps and portals can enable information pathways that connect vulnerable populations to critical care, resources and infrastructure services. RADTs help physically distanced communities develop a sense of belonging, sharing, and self-efficacy while incrementally building shared knowledge over multiple crises and stimulating resilience.

As we move forward…

We have experienced SARS and are now in the throes of COVID-19. SARS taught us valuable lessons about the use of IT during a pandemic. At the time, RADTs were largely overlooked. In responding to COVID-19, it is time we explore how these enabling technologies can ease the way forward. Can they help one community rapidly learn from another? Can they surface vulnerabilities within and across communities? What types of public policies and education programs are needed?

RADTs are certainly not silver bullets. Investing in resilient infrastructure is just as important, since communities depend on public digital infrastructure for access to the internet and other telecommunication networks. We can learn from the past as well as from resource-constrained environments in developing countries to build affordable, sustainable, inclusive infrastructure.

But we should not lose sight of the need to consciously involve communities across Canada in generating their own responses—to help them envision their own solutions delivered with digital technology.

Suchit Ahuja is an assistant professor of business technology management at John Molson School of Business. Yolande Chan is E. Marie Shantz Professor of IT Management and Associate Dean (Research, PhD and MSc Programs) at Smith School of Business. Arman Sadreddin is a Ph.D. candidate in management information systems at Smith School of Business, who will join the John Molson School later this year.