For Digital Innovation, Product Meaning Rises to the Top

How to manage the three tension points that can drive digital product design to new heights

Apple’s iPad gets most of the credit for defining tablet computers and redefining the computing experience. But the history of tablet computers goes much further back.

In 1957, Bell Laboratories demonstrated Stylator and in 1964 Rand Corporation created Rand Tablet. Both established handwriting with a stylus and touchscreen as new ways of interacting with computers. In 1989, Wang Laboratories’ Freestyle and GRiD Systems Corporation’s GRiDPad represented early attempts to tap into the convenience of handwriting technologies for information processing tasks.

In 1993 and 1996, Apple announced MessagePad and Palm Computing released PalmPilot. These iconic products pushed portability to an unprecedented level—the so-called “palmability,” which, together with communication capabilities and personal organizer applications, provided consumers with instant access to information.

All these products featured technological excellence. All were business failures.

And then there was the iPad. The iPad was based on Steve Jobs’ 1983 visionary interpretation of a tablet computer as “a book that you can carry around with you and learn how to use in 20 minutes.” Animated by this definition, Apple designed and redesigned the iPad’s components to ensure the interaction with the touchscreen, the appearance of the device, the operating system and applications, all served the intended meaning of the product.

In 2010, the product that emerged from all this fussing was a “breathtakingly simple” device that was highly mobile and fully intuitive, establishing tablet computers as a realm of computing for everyday information processing.

Reimagining new meanings

The story of tablet computers carries an important message. It illustrates how truly historic digital product innovations are often those that rethink the nature of a product, re-imagine new meanings for it and allow the new meanings to drive its design.

Today, more than ever, product meaning is a crucial aspect of digital product innovation. Thanks to modularization and miniaturization, digital technology can be embedded in virtually any product imaginable. As a result, familiar products attain new meanings. Digitally-enhanced footwear with fitness tracker software, for example, prompts us to rethink shoes as more than just “a covering for the foot.” Traditional underwear imprinted with electrochemical sensors is given new meaning as a “health-care device.”

Despite the importance of product meaning to digital product innovation, few firms pay attention to it. Most approach digital product innovation as a problem of functionality. In this functionality mindset, the value of a product and its design typically resides in engineering, which emphasizes that a product is designed to solve a functional problem. Any solution is evaluated against functional measures of “validity, utility, quality and efficacy” based on objectives defined by intended user groups.

Limits of a functionality mindset

The functionality mindset is limiting in that it is concerned with creating a digital product for an identified problem. Although the design process is considered important, the focus is on improving the understanding of the identified problems and criteria. This approach risks turning the product designer into a reactive rather than a proactive agent.

More importantly, although functional novelty and superiority are imperative for technological innovation, they are just a necessary, initial condition. Google learned this lesson the hard way with the failure of Google Glass.

Google’s brand of smart glasses was a voice- and motion-controlled device that users wore as eyeglasses and that displayed information directly in the field of vision. Despite its original promise to transform our lives, Google Glass failed to go beyond mere “tech coolness” to fulfil the expectation of a device for “daily experience”. It was neither cool (when looked at from the outside of the lens, the wearer’s eyes looked weirdly twisted) nor something that could be used as part of daily living (people wearing Google Glass were banned from some bars, restaurants and even pet stores).

Although the product boasted multiple innovations, the functionality mindset unwittingly blinded designers to the incompatibility of the technological innovations and the intended product meaning.

Handling the three tensions

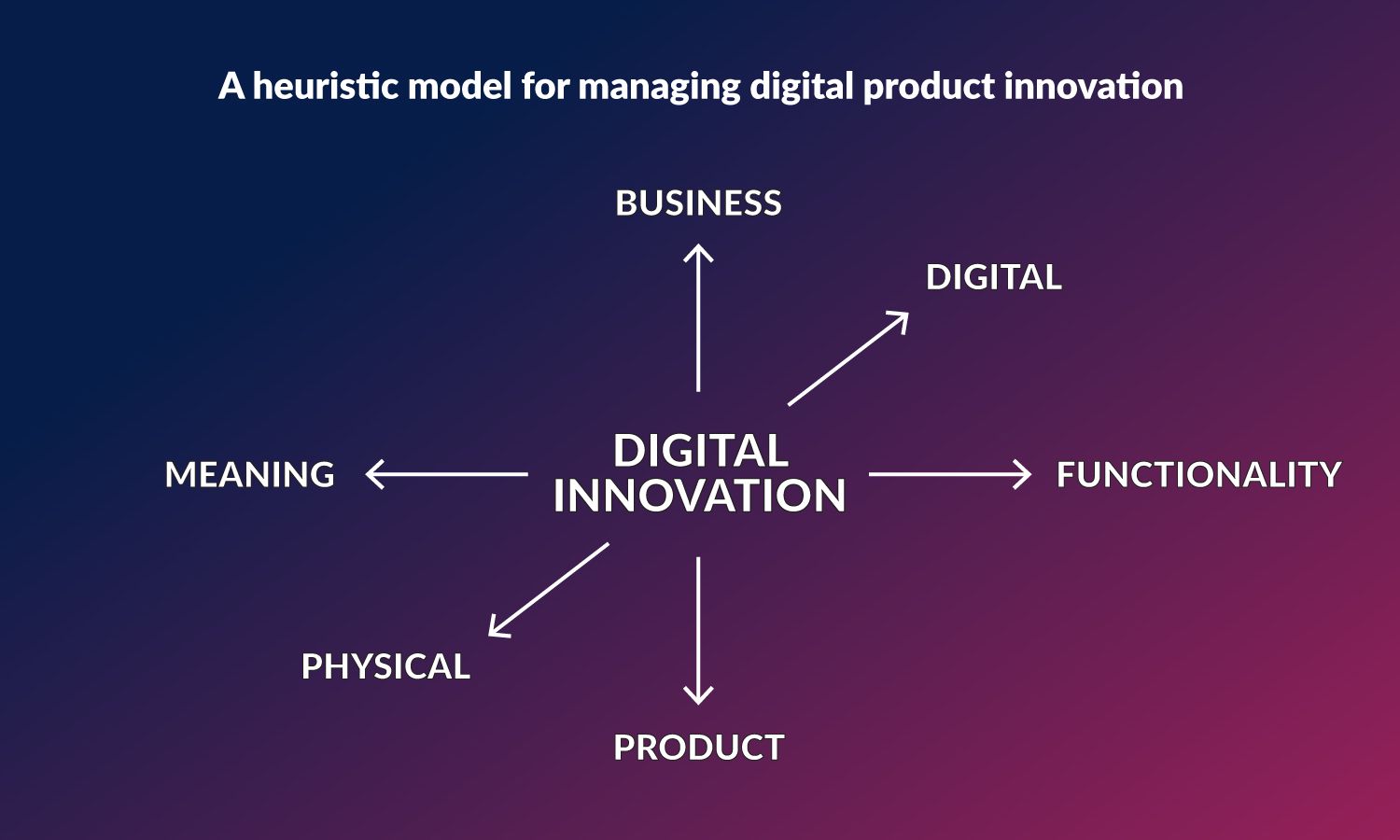

To ensure product meanings maintain their place in the digital product innovation process, a research-based model that I helped design serves as a useful heuristic tool. The model suggests that to identify and capture opportunities in technological innovations, digital product innovators must handle tensions along three dimensions. Have a look at the model in the diagram below. Then let’s use real-life examples from the product design world to help us understand how the three dimensions play out.

Functionality versus Meaning

Functionalities provide the raw material for product meanings, while product meanings enable and constrain how functionalities are created and interpreted. Let’s illustrate using the iPad: On one side are the functionalities of “information storage,” “portability” and “intuitiveness” that ground the product meaning of “a book that you can carry around with you and learn how to use in 20 minutes.”

On the other side, the intended product meaning focused the innovation team on these three functionalities rather than on other functionalities such as the largest storage, toughest case or highest-resolution camera.

As product functionalities ground product meaning, and product meaning defines what product functionalities are relevant and how they should be implemented, digital product innovation is always subject to tensions between them. Failing to manage these tensions well can result in a failed or confusing digital product.

Digital versus Physical

It is an engineering platitude that digital and physical functionalities must be compatible. If a tablet computer cannot be touched, for example, it cannot accurately track fingers and parse gestures. Less recognized but equally important is the compatibility between digital and physical meanings.

The failure of Google Glass can be traced to the conflict in meaning between physical and digital components. The physical component, the glasses, is commonly understood as a tool for “use on all private occasions,” worn anytime and anywhere, whether it is in the bedroom or bathroom. Digital components such as digital cameras, microphones and network connections are understood as devices for “information collection and sharing.” The physical and digital meanings are wildly incompatible, and this explains why consumers were spooked about their privacy being compromised.

Had Google designers attended to the tensions along this dimension, they would have evaluated digital and physical meanings and decided whether to have the “use on all private occasions” or “information collection and sharing” product meaning drive the design.

Product versus Business

Tensions along the product-business dimension result from the need for new digital products to make sense to an existing group of consumers (a “smart speaker” must at least be a speaker) without allowing the old product meaning to dominate product design.

Letting old product meanings dominate product design can lure digital product innovation teams into repeating old design logic. It can also blind firms from realizing emerging opportunities for technological innovations and new product meanings.

This partly explains the failure of Apple’s and Motorola’s ROKR phones. The product was confined by the established market meanings of mobile phones as a device for making phone calls, making it hard for Motorola to appreciate the need for larger music storage. Similarly, Apple was so fixated on viewing iPods as a peripheral of computers that it overlooked the potential opportunities from iPods tapping into a mobile network.

Digital product innovators can use this simple tool to broaden their functionality mindset and incorporate product meanings into their design work. It is particularly useful for the redesign of traditional products into digital products that must wrestle with established business traditions and physical functionalities.

The goal here is to work on each tension point in a mutually compatible and reciprocally reinforcing manner. There is usually no predefined start and end of this process. Rather, firms must iteratively travel back and forth between the two ends of each dimension throughout the design process until they settle on the sweet spot.

Gongtai Wang is an assistant professor in digital technology at Smith School of Business.