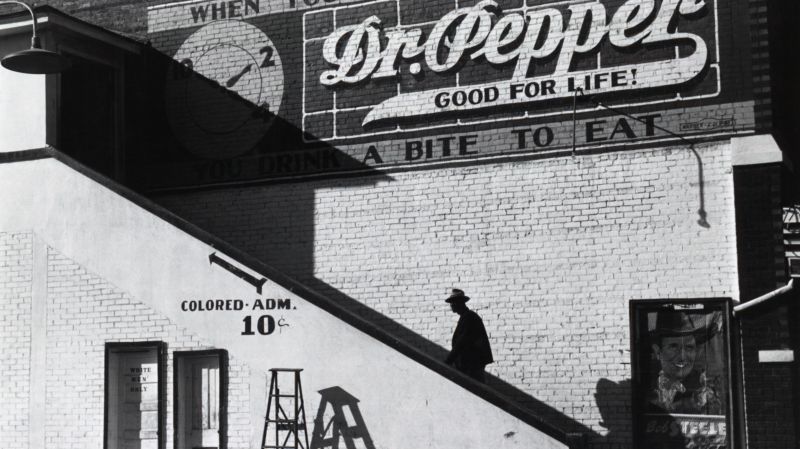

Why The Stain of Segregation Was So Hard to Remove

Not even the profit motive could counter the segregation of American theatres

Visitors to Atlanta can see a stark reminder of the Jim Crow era, when racial segregation in the United States was enforced by state and local laws and social mores. At the Fox Theatre, you can still walk up the three-storey staircase on the south side of the building to the “crow’s nest,” the cramped balcony where black patrons were allowed to sit after they bought tickets at a separate box office. A white wall still partitions the balcony from the main section of the theatre.

This sorry era of segregation lasted from 1877 to the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, and wasn’t limited to the Deep South. While the social history of segregation has been well told, the economic history still has chapters to be written. Consider the question of how businesses responded to segregation. As Ricard Gil, professor of business economics at Smith School of Business, points out, restaurants, shops, and other businesses often excluded black patrons even in defiance of city ordinances banning segregation. What motivated their discrimination: were they acting out of their own beliefs or did they fear losing their white clientele?

To find out, Gil teamed up with Justin Marion (University of California, Santa Cruz) to conduct a series of studies that looked at the economic dynamics of movie theatre segregation in the 1950s. “It was a time when explicit segregation was still common in southern states and some theatres still refused to show movies with black actors playing prominent roles,” Gil says.

Follow The Money

In trying to tease out whether theatre owners or white audiences were driving discriminatory practices during that time, Gil and Marion focused on basic business principles. They figured that if business owners really wanted to discriminate against black movie goers — and thereby exclude a potential audience — they would do so knowing that they would sacrifice revenue. Therefore, when owners would be forced by law to desegregate, their profits would increase as more black movie goers would patronize the theatres.

Alternatively, the theatre owners may have preferred to desegregate but were constrained by the preferences of their white customers. In that case, when theatres were desegregated, white customers would vote with their feet and the profit of theatre owners would go down.

Gil and Marion discovered an inspired way to solve the puzzle.

Prior to 1953, segregation in Washington, D.C. was widely practised in movie theatres, restaurants, and other private businesses, but it was by the choice of the business owners rather than backed by law. In fact, as Gil points out, anti-segregation laws were enacted by the local government in 1872 and 1873 but unenforced. In 1950, they became the basis of a legal challenge brought by a number of customers who were denied service at a local restaurant. The lack of enforcement was challenged — successfully — in the courts. The subsequent Supreme Court ruling in 1953 agreed the laws would have to be enforced.

This historical footnote gave Gil and Marion the opportunity to test their hypothesis. Since the ruling only applied to the District of Columbia, the researchers compared revenues at each movie theatre in Washington, D.C. before and after the Supreme Court ruling with revenues at theatres in 25 other cities. They figured that if theatre revenues in Washington dropped as a result of desegregation, it was likely because the owners were kowtowing to their white customers. If revenues grew, it would show that the owners were committed to segregation themselves, even at the cost of potential revenue.

Gil and Marion harvested data from Variety magazine; this trade journal published weekly information for each theatre on how much revenue was earned, what prices were charged, and which films were screened.

Studying the data, they found that revenues of Washington theatres fell by around 10 percent after desegregation relative to theatres in other cities showing similar movies. The timing of the revenue response matched the date of the Supreme Court ruling.

“And that’s net,” says Gil. “So that means 20 to 30 percent of white patrons choose not to go” to these theatres after desegregation was enforced.

Gil and Marion were also able to look at the issue from another angle: the screening decisions made by theatre owners. They figured that if theatre owners were motivated to discriminate, they would be less likely to continue the run of a movie with a black cast member versus one featuring an all-white cast.

For movies shown during that time, they obtained information on the racial makeup of a film’s cast, including the importance of each actor’s role. They then cross-referenced that data with revenue information on each theatre as well as racial bias of each city in question (drawn from public opinion polls conducted in the late 1940s and 1950s and that contain respondents’ race, state of residence, and the response to questions related to racial attitudes).

The result: movies with black actors earned around 11 percent less revenue and were screened for fewer weeks in cities with greater racial bias.

Gil says the conclusions are clear: “Together our results suggest that customer discrimination likely played a central role in the practice of segregation.”

Black-Owned Theatres Fill The Gap

Shut out of mainstream theatres, it is not surprising that a substantial number of theatres serving black customers opened during the latter years of segregation (though it was much more difficult to obtain credit or city registration to start a business). In an earlier study, Gil and Marion showed that residential segregation led to more black theatres than expected given the size of the black population and the socioeconomic characteristics of the area. This is consistent with many other studies that show residential segregation is good for small businesses: local stores that cater to specific groups are less likely to compete with stores downtown.

The mainstream and black-owned theatres were separate but hardly equal. As Gil points out, theatres catering to black communities were inferior in many ways. Often, they were converted houses that were not in great shape in begin with.

“They often showed more second-run movies and were less likely to offer amenities,” he says. “It was rarer, for instance, for an African-American theatre to be air conditioned, and in the early years of cinema it was less likely for an African-American theatre to have sound.”

—Alan Morantz