Making Productivity a Priority in Canada

Driving greater prosperity and growth depends on leaders pulling the appropriate levers to increase value and reduce waste

There’s an old saying that everyone complains about the weather, but no one does anything about it.

We could say the same about productivity in Canada, which is in decline. Admittedly, the most common complaints do not refer to our productivity malaise itself, but more often to the symptoms of poor national productivity. Our taxes are too high! We can’t find workers! Our health care and education are underfunded! And do we really need massive government incentives to spur companies to invest in domestic manufacturing?

We need to do better. But how?

It helps to first understand the definition of productivity. A measure of economic productivity is the rate at which the output of goods and services is produced for each unit of input. More output for the same input is better productivity; less is worse.

When you extend that output to individuals, organizations and the country, it reflects our ability to pay. That is, greater productivity gives us the ability to afford the goods and services we rely on. It funds health care, education, our military, government and infrastructure. In organizations, greater productivity can free up labour, improve customer and employee experiences and distinguish firms in competitive industries.

One way to think of the significance of productivity is with this simplified formula:

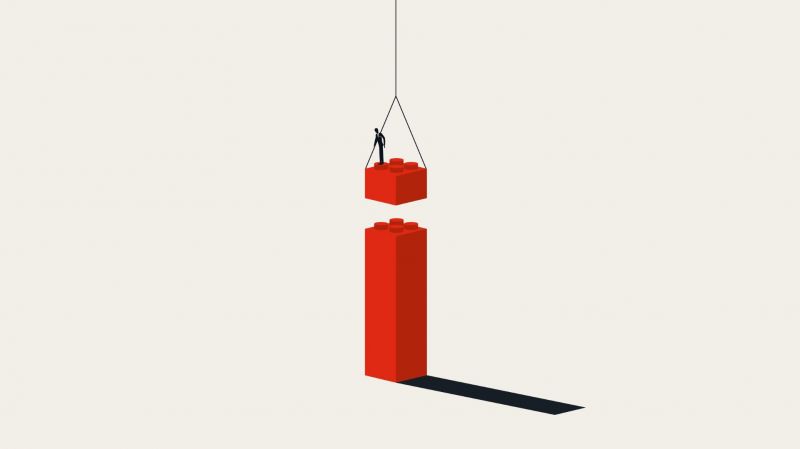

Prosperity and Growth = Value Created − Waste

Driving greater prosperity and growth relies on leaders pulling the appropriate levers to increase value and reduce waste. We think of value when we enjoy or benefit from a particular product or service, but value also encompasses improved perspectives, knowledge or even connections, which enhances the entity holistically. Waste is easier to identify: Rework, returns, work we don’t get paid for, legal and regulatory elements and, especially, sub-optimized processes are all elements of operations that destroy value.

Greater productivity attracts further investment, and its absence has led to organizations pulling out of Canada or failing outright. This summer, Kimberly-Clark’s iconic facial tissue brand Kleenex disappeared from store shelves and the company stopped manufacturing the product in Canada, citing the “unique complexities” of the market despite their “best efforts.”

Department store chain Nordstrom announced it was leaving this year as well, also noting that their “best efforts” had failed. Home improvement retailer Lowes made a similar announcement a year ago. When we accept these examples as an organization’s “best efforts”, we endorse mediocrity.

Granted, doing business in Canada comes with some challenges. They include dual-language labelling and marketing, metric units of measure, separate financial and tax reporting and, of course, a small population spread across a large land mass.

Yet, despite these obstacles, many organizations from other countries have figured out how to do business here. Home Depot has been incredibly successful in Canada, as has Walmart. They are now as much a part of the retail fabric of the country as Canadian Tire, though with admittedly less local community support and engagement. There is an entrepreneurial spirit that is alive in organizations that succeed, but also a relentless pursuit of productivity.

While commitment to productivity in Canada has languished, other countries are going all in, investing in productivity, capability and a “build here” culture. Productivity in Australia has improved over the last two decades, and the Biden administration has committed billions of dollars to improving American productivity. We should expect and demand no less from Canadian politicians and public investment.

Automotive and parts manufacturing operations have expanded in Mexico. Twice as many cars are now produced in Mexico than 15 years ago. The country has signed 40-plus free trade deals that enable car companies and other producers to save 10 per cent over Canada when shipping from Mexico. In Canada, we struggle with trade between provinces (B.C. wines, Alberta beef, for example).

Until we begin to honestly invest in productivity, and the way we work in Canada, we will continue to see organizations exit the market. This cycle is indeed vicious. Fewer organizations in any sector leads to less competition and weaker incentives for investment in productivity. We’re already seeing this dynamic in industries such as banking, telecom and groceries, where three to five large companies dominate.

What could better productivity look like? For consumers, it would show up as:

• Lower fees in banking and telecom

• Lower prices at the grocery store

• Greater selection as more organizations operate in Canada

For producers, improved productivity includes lower costs, a greater output per unit of labour and, often, reduced investment in capacity. In fact, capital investment should happen only after optimizing existing operations. Dysfunctional processes are organizational kryptonite.

What should government do?

The announcement in November that the Stellantis battery plant being constructed in Windsor, Ont., would require up to 1,600 temporary foreign workers from South Korea to launch the facility was eye-opening. These are technical employees, skilled in the equipment and processes necessary to manufacture electric vehicle batteries. The news presumably suggests that those skills and intellectual property do not exist in Canada. While the plant may eventually employ up to 2,500 hourly workers, those will be lower-skilled manufacturing jobs.

Recent announcements of federal and provincial subsidies in facilities being built near Windsor, London and Kingston, Ont., and most recently in Maple Ridge, B.C., are part of a larger strategy to establish Canada as a global battery-making centre. That may make sense in the long term. The intellectual property and skills necessary to design and launch such facilities and other high-tech manufacturing, however, need to be part of our portfolio.

Government spending must be directed more at enabling and less at giving. After all, the recent fall budget update included a $40-billion deficit, which means we are borrowing money to service these subsidies and $46 billion in debt servicing charges. Greater national productivity would fund these investments and spending.

So what should government be doing to help? Let’s start with these three steps:

• Invest in the curriculum necessary to support technical training in sectors such as manufacturing, health care, fintech, artificial intelligence and communications. We need top-to-bottom skills, research and training in areas that will drive growth over the next 10 to 20 years.

• Simplify the visa and work permit process for skilled workers already in the country. I recently bought my wife a gift at Holt Renfrew in Toronto and had a nice discussion with the young man helping me. He told me he has a degree from Hong Kong to teach high school physics but that navigating Canada’s cumbersome permit process has so far taken him over a year. My Uber driver the same day was a mechanical technologist from Ukraine. International students studying at Queen’s University, where I teach, tell us the student visa process takes longer in Canada than in most other countries open to them.

• Fund or otherwise subsidize companies looking to upskill their workforce with integrated internships, especially those that enable greater productivity and capacity or that bridge industries such as health care and engineering. Many small and medium-sized enterprises don’t employ true operations people. These firms need support to build these skills.

The role of industry in productivity

A common question I hear from organizations is, How do I know when we have a productivity problem? Some of the symptoms include backlogs, queues and delays; unclear outcomes to a process; employee morale issues or high turnover; staffing shortages; the same customer complaints over and over; and, ultimately, an environment in which you are competing on price.

In a larger sense, productivity is also an issue when your customers can’t tell the difference between your organization and that of your peers, or when there is nothing special about your product or service. Seth Godin once said that if you can’t imagine a world where people are fascinated by your product (or service), it’s time to move on.

Here are three tactics that businesses should consider for growing their productivity:

• Invest in skills and technology. Partner with a local college or university and commit to hiring one or two graduates from a program per year. Create internships for students still in the program. Also, make sure you have at least one process guru in-house. These people pay for themselves in efficiency, savings and new capacity.

• Identify and pursue your “best-ness”. Thinking of Godin’s quote above, do you give customers a reason to do business with you? If you can’t define it, build that best-ness. Perhaps your edge can be your productivity. That was a focus for one of the companies I worked at back in my industry days, and it was a successful strategy.

• Observe, measure and talk about productivity. Put metrics on your dashboard. You should be able to see every day how productive your operations are. And then, coach, invest and lead accordingly.

Investment in productivity pays for itself. That includes investments in innovation, operations, technology, engineering, trades, internships and employee development. At the government level, investment in education, transportation and communication infrastructure and the movement of natural resources to market all enable and support greater productivity.

I have been studying, practising and talking about productivity for years, in companies, classes and keynotes. This is not a complicated subject. If your organization is not pursuing productivity improvements relentlessly, you are missing out, and your customers or constituents are paying for it.

Barry Cross is Distinguished Faculty Fellow of Operations Strategy at Smith School of Business and author, most recently, of Simple: Killing Complexity for a Lean and Agile Organization.