Leadership in 556 words

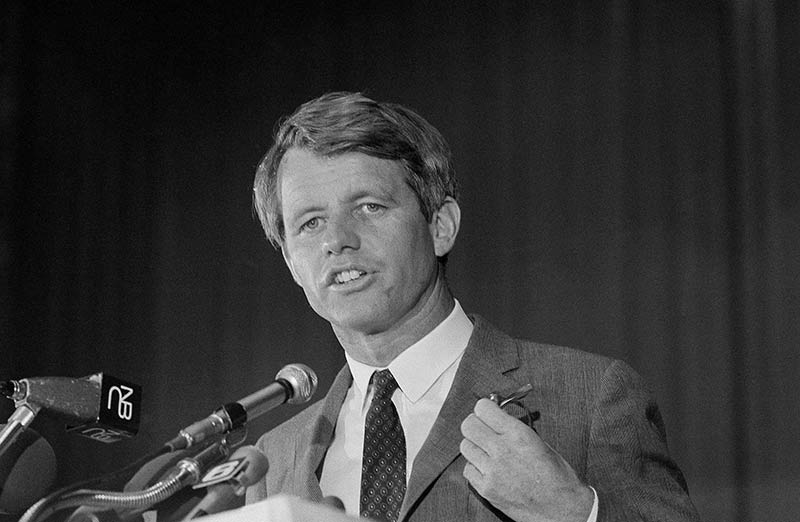

Robert Kennedy announces the death of Martin Luther King on the night of April 4, 1968

I was still a high school student in South Africa in 1966, when Robert F. Kennedy’s brief visit to South Africa electrified the anti-apartheid movement, and terrified the apartheid government. RFK, then a United States senator, was hardly known as a gifted orator, especially when compared to his brother, President John F. Kennedy, who had been assassinated two-and-a-half years earlier. Still, RFK’s visit to South Africa is mainly remembered for his remarkable “Ripple of Hope” speech at the University of Cape Town. Starting with disarming, self- deprecating humour, when he noted the similarities rather than the contrasts between South Africa and America, RFK used a metaphor that has stood the test of time to paint a picture of what might be achieved in South Africa.

Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centres of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

Despite this speech being regarded as one of the greatest in political history, it is not the one most closely associated with RFK. That honour goes to the speech he delivered in Indianapolis on April 4, 1968, when he informed a crowd of mostly African-Americans that Martin Luther King Jr. had just been assassinated.

RFK was supposed to deliver a campaign speech that night. A few weeks earlier, he had announced that he was running for president. So the crowd that came to hear RFK in an African-American community in Indianapolis was expecting a political rally. But just hours before RFK arrived, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot in Memphis (where he had gone to support striking sanitation workers) while standing on the balcony of his motel room. After learning that King had succumbed to his injuries, the police advised RFK not to address the thousands of people who had already gathered. The police feared that they could not guarantee his safety given how angry the audience might become after learning that King had been assassinated. But RFK went ahead anyway, knowing that it would be up to him to deliver the tragic news.

How can we understand RFK’s speech? Research by leadership scholar John Antonakis and his colleagues provides a framework for understanding the power of this speech. Charisma, they tell us, comprises a set of nine verbal and three non-verbal behaviours. Verbally, charismatic leaders use metaphors (and other figures of speech), they tell stories and share anecdotes, they are rooted in moral conviction, they share sentiments of the collective, communicate confidence, heighten contrasts to draw attention to their message, use lists, and ask rhetorical questions. At the non-verbal level, their voice is animated, and they use both bodily gestures and facial expressions that reinforce what they are saying.

At this stage you would be forgiven for throwing up your arms, believing that there is no way anyone could accomplish all that. The good news is that leaders don’t need to do “all that”—nor should they try. Indeed, research shows that leaders can be too charismatic for their own good. Not even RFK used all 12 charismatic behaviours. Instead, RFK’s use of three charismatic behaviours (sentiments of the collective; the use of contrasts; and an animated voice) was enough to influence the crowd to just go home.

Facing the predominantly African-American gathering, it was critical for RFK to reduce the distance between himself and the crowd. One way he accomplished this was by using sentiments of the collective—in this case by mentioning his own brother’s assassination in reference to King’s murder. He told the crowd: For those of you who are Black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man.

Towards the end of his speech, he again draws people closer together, reminding those gathered that despite the massive racial divisions in the country (or maybe because of them): ...the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of Black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings who abide in our land.

Foreshadowing Nelson Mandela, RFK knew that the best of leadership was not about making everyone in attendance love him, but rather drawing them closer and closer to his vision.

Robert Kennedy on the presidential campaign trail in 1968

Another major feature of RFK’s speech was his exquisite use of contrasts to reinforce his message and give people a choice of which direction they wanted the country to go in. He said: In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are Black . . . you can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization—Black people amongst Black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another. Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love.

A little later, RFK offered a call to action for a better America: What we need in the United States is not division . . . is not hatred, violence or lawlessness; but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be Black.

What RFK was doing was deliberately using contrasts to create a greater sentiment of the collective.

Another crucial aspect of RFK’s speech is his voice. It’s utterly gripping. Antonakis and colleagues suggest that charisma is reflected in an animated voice. But when you listen to RFK, you will appreciate that his entire speech is a shining example of a calming voice in the midst of the storm. Don’t be misled by his almost monotonic presentation. Focus instead on how his frequent pauses gave the audience a chance to catch their breath and reflect on his message.

Something else adds to the power of RFK’s speech—its brevity! Remarkably, his speech is a mere 556 words. In one of the 10 most watched TED Talks in 2021, Smith alumnus and current London Business School professor Niro Sivanathan, MSc’02, Artsci’01, reminds us that when it comes to influencing others, brevity is key. Including non-relevant, extraneous information is not just ignored, it detracts from the main message. In Indianapolis, RFK spoke directly with his audience. Not a word was wasted.

The power of RFK’s speech is evident from what happened when he finished. Racial rioting broke out in virtually every major city in America when people learned of King’s death. But the people of Indianapolis just went home. (Alas, RFK would be gunned down two months later.)

Aside from its obvious historical importance, RFK’s speech has invaluable lessons for our own leadership today. So what can we learn?

Let’s start with those 12 charismatic behaviours that the researchers identified. “But I can’t do all 12 of them,” you might say! Nor should you. Recent research reaffirms even using a few charismatic leadership behaviours will help you be more influential. That being the case, are some charismatic behaviours more important than others? The good news is that there is simply no evidence that some are more important; instead, whichever you do choose to use, just ensure they are authentic expressions of yourself.

Martin Luther King delivering a speech in Atlanta in 1960

Speaking of authenticity, you may wonder about the professional speechwriters who fed RFK his words that night. Once again, you may point out, “I don’t have speechwriters!” And you don’t need them. After all, RFK didn’t. One of the remarkable aspects of RFK’s Indianapolis speech is that he wrote it himself in the time taken between leaving his hotel and arriving at the venue. He did have a formal campaign speech written, but ditched it when he realized that it would be totally inappropriate. And RFK did not read his speech! He literally spoke to the audience, cementing the bond between them and him.

Another factor that may spring to mind is charisma. While many people believe that charisma must surely be something that some lucky people are born with, this is not the case. Here again, RFK is Exhibit A. Though he certainly possessed some of the Kennedy family charm, RFK was not a natural speaker. Few ascribed to him the soaring eloquence of history’s greatest speechmakers, like his brother, JFK, or Martin Luther King Jr. But as RFK demonstrated, each of us can learn to use some of the charismatic leadership behaviours, which will be more than enough to enhance our influence.

But are the effects just limited to speeches? No. There is every reason to believe that we can be charismatic in emails as well. Contrasts, metaphors, lists, sentiments of the collective and asking rhetorical questions—all of these can be used to make your emails more influential.

Taken together, what does RFK’s speech teach us? The very best of charismatic leadership is about the smallest things you do, at the right time, to help people re-imagine a better future for themselves and others. Especially in their darkest moments.

Julian Barling is the Borden Chair of Leadership and Stephen Gyimah Distinguished University Professor at Smith. He is an authority on transformational leadership and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. He is the author of 15 books, including the forthcoming Brave New Workplace: Designing Productive, Healthy, and Safe Organizations.