A mountain to climb

In 2012, Michael Schauch, AMBA’07, and his wife, Chantal, headed deep into the Himalayas of northern Nepal. Their destination: the Nar Phu Valley, a remote region closed to outsiders for decades that was just then being opened to visitors.

With them was a team of artists—a photographer, musician and painter. Together, they wanted to document the isolated villages of the valley before the inevitable encroachment of people from the outside altered the valley forever. “We wanted to capture a moment in time, before it was gone,” says Schauch, who lives in Squamish, B.C. and is vice-president and portfolio manager with RBC Wealth Management.

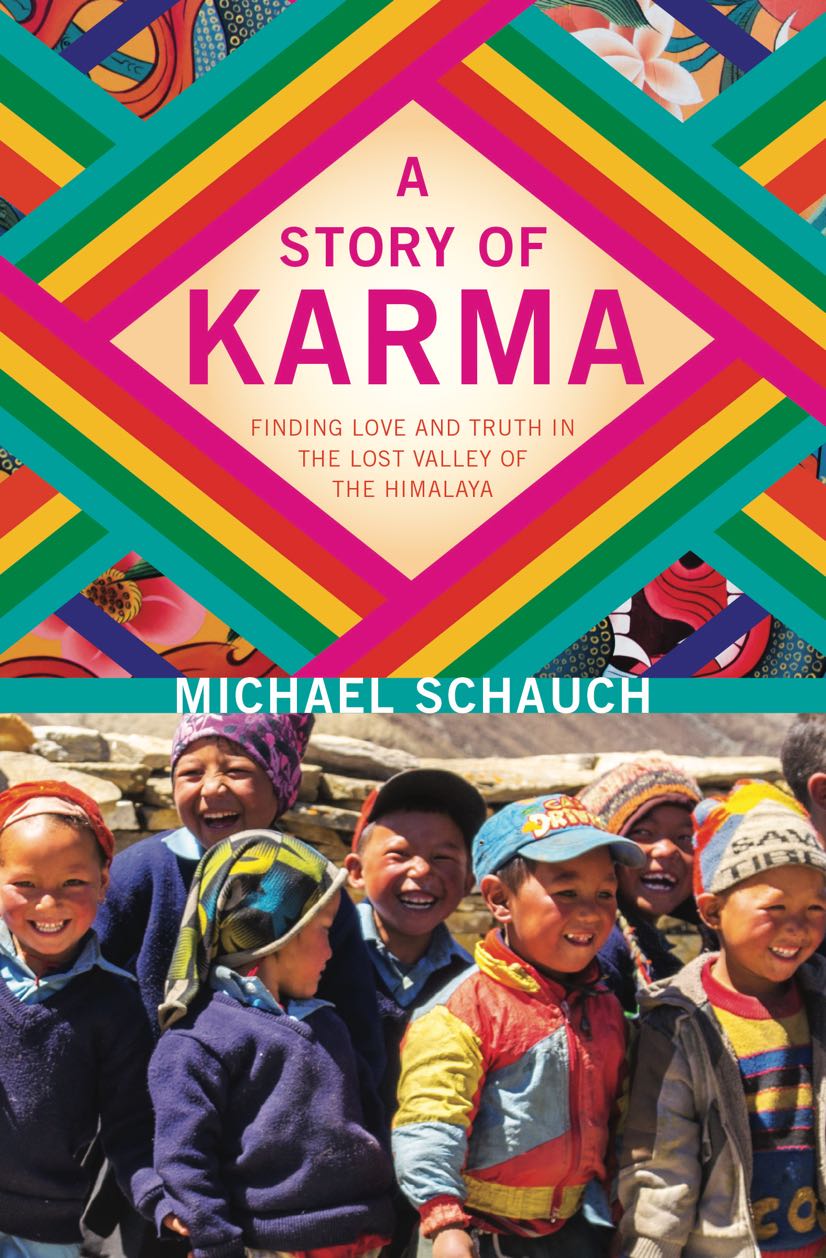

But Schauch had another motive for the trip: to climb an unidentified peak he’d only seen in a photo. An experienced mountaineer, Schauch was captivated by its pyramid shape and sharp ridgelines. Adding to the allure: it wasn’t clear that the mountain had a name or if anyone had ever climbed it. “Some mountains just pull at me,” Schauch says. “I can’t tell you why. I just have to climb them.” In Nepal, the mountain and the people around it would change his life. It’s a story Schauch tells in his book A Story of Karma: Finding Love and Truth in the Lost Valley of the Himalaya [Rocky Mountain Books], published this fall. In this excerpt, he writes about his attempt to climb the 21,995-foot (6,704-metres) mountain.

Outside the snow crystals danced in spirals, as if stirred by an invisible angry force. Some eventually came to rest on the ground, blanketing the landscape. Others returned to the sky, becoming lost in the infinite white that had now become our world.

My two Nepali guides and I had taken refuge in the ruins of an ancient stone hut. It was one of a number of huts—in varying degrees of collapse—that must have once been part of a great village, though all other signs of human habitation had disappeared. We sat in silence on the frozen dirt with our backs to the wall, looking out through what would have been a doorway but was now just an empty space, listening to the mountain winds exhale. Towers of ice and rock as high as 7,000 metres surrounded us like a fortress. They held the authority out here. The three of us, IC, Ngawang and I, were deep in the remote Himalaya of northern Nepal, isolated not just from the rest of the world but also from our companions—my wife, our three friends and the other members of our team—who had remained behind. They were in a village not far away, but at the moment they might as well have been on the other side of the world, our aloneness seemed so complete.

Some might have wondered why I had gone through so much effort, time and money to venture into this desert of ice and rock in one of the most far-flung, inhospitable and even dangerous places on Earth. I know my parents had asked me the question enough times. I could never really give them a reason. The mountains called to me, and I went to them. I’d been answering that call in many places over many years, though never in a place as remote as this.

Children playing in Nar, a village in the mountains of Nepal.

My wife, Chantal, who was further down the valley, waiting for us to return, had tried her best to support me on this expedition, as she had on so many others. She understood how important it was to me, and she had wanted me to climb my mountain. But I never imagined this journey would take such a severe toll on her. Although she had gone on a number of these expeditions with me, including a recent one that she herself had suggested to Mount Kilimanjaro, trekking through these mountains in the thin, high-altitude air had been much harder for her, both physically and mentally, than either of us had anticipated. It was my ambition that had brought us here, and now it had taken me away from her, away from what mattered most. A shiver ran up my spine. I pulled the collar of my jacket over my mouth and breathed into it, feeling the warmth for a moment against my neck.

“What is this place?” I wondered aloud, speaking to no one in particular.

Ngawang’s eyes narrowed, studying the wall in front of us, as though each of its stones had a story trapped inside. “This place is empty. Villagers left long time.”

Our hut was no more than four walls of rock stacked about two metres high, bound together by caked mud, with a roof also made of stones, which was supported by wooden beams. The stones were rough and cold to the touch. The whole place smelled of ice and earth. It smelled old. A single ray of light reflecting off the snow outside lit the dim room through the opening at the front.

My eyes traced a crack in the rock wall that ran from the dirt floor up to the beams above me. The beams were also fractured, some of them nearly split in two and caving in from the weight of the large flat stones of the roof. The whole thing looked like it was destined to collapse on us at any moment. But it wasn’t the thought of being buried by the rocks that bothered me most—it was the possibility that no one would ever find us here, amid the many other piles of rocks in what was left of this Himalayan ghost town.

The remnants of the village appeared to be centuries old. The rocks of which the houses had been constructed were reduced to rubble, weathered and faded, covered in red lichen and inscribed with Tibetan etchings unlike any we had seen before, as though from another era. These few human-made markings would soon become invisible, time and weather erasing all traces of the people who had lived here under what must have been extreme hardship.

The only sign of life we had encountered nearby was the print left by a snow leopard. We had discovered it just before getting trapped by the storm. I took comfort in thinking about the snow leopard—a creature that had somehow managed to live within this barren, isolated place. I had imagined it watching us as we fumbled our way forward through the blizzard. How very different it was from me—a living being as fluid as a mountain stream, and as ghostly as the summit we sought to climb. Yet for all our differences, I felt a kinship with it, a sense that both of us had been called to the mountain that loomed above us, that this was where we were both meant to be.

Mike Schauch in the mountains of Nepal.

And it wasn’t just any mountain. It was the mountain. A perfect pyramid from its southwest aspect, with sheer faces and a striking ridgeline that snaked its way to a spear-tipped summit piercing both cloud and sky. It was a mountain out of a storybook. I yearned to feel it beneath my feet. To climb it, to experience it, to learn from it, to be part of it—even if only for a brief moment. It had won my heart and beckoned me to come to it. It was a jewel of the earth, buried deep in the Himalaya. And I had found it.

From the moment I first saw it—in a photo a friend had shown me in a restaurant some months before—I couldn’t stop thinking about it. It was a place I seem to have imagined in my dreams; one I felt I had to find in real life. The pyramid mountain drove me into a fit of mountain frenzy—one that consumed me, forcing me on a mad quest into one of the most inaccessible corners of Nepal, where we had come up against a wall of mountains called the Lugula in the upper Manang district, a distant subrange of the Himalaya that formed part of the border between Nepal and Tibet. Thrust up from the Tibetan plateau, the chain of 6,000 to 7,000-metre jaw-dropping peaks formed a serrated horizon so high that even the clouds gazed up to it.

Yet for all the awe I felt in the presence of these Himalayan peaks, there was something equally powerful about the valley where our companions were now sheltering. I had felt something there I had never experienced before—a sense that I had travelled into another world, but also that it was a world I’d been to before. It was as though I was a time traveller from the future who had stumbled my way back into a different epoch, one I had somehow known in an age long forgotten and was meant to return to.

The few mountain dwellers we had come in contact with over the previous days had reinforced these strange sensations. I’d seen them only briefly as we passed each other on the mountain paths. But I’d felt drawn to them, as if they possessed some deep wisdom I’d lost but could learn again if only there were time. Yet we had forged past them, driven by my compulsion to keep moving, venturing ever deeper into the mountains, until they became mere dots of colour against the barren landscape, and then disappeared entirely.

They left my sight, but they did not leave my heart. Who were these Himalayan wanderers? What pulled me to them? I had so many questions. Questions that seemed destined to go unanswered, for my focus on the pyramid mountain was absolute, and I was determined that nothing would get in the way of my ambition to scale it.

We’d been trekking for nearly two weeks by then with our companions, and then venturing out on our own, on this mission to find the pyramid mountain, for the last two days. During these two days alone, my Nepali guides and I had crossed many distant rivers and explored outlying valleys and ridges, had covered 30 kilometres and ascended nearly 1,850 metres. I had spent over 15 years training in the mountains to be in a place like this, to climb that mountain that lay so tantalizingly before us—only to find myself caught in a snowstorm.

As I contemplated our next step, the snow crystals outside began floating their way across the exposed threshold, turning to frost on my face and numbing it. Even with my merino wool base layer, microfibre fleece, 800 goose down-filled jacket and windbreaker, I was cold. My body was starting to feel fatigued, partly from the chill that was sapping the energy out of me, and partly from the 5,030-metre elevation, which was making me feel short of breath.

The longer we stayed here the worse it was going to get. We had to leave. I peered outside. Our plan to wait out the storm had failed; it was clear the snowstorm wasn’t going to let up.

I looked over at IC and Ngawang. Their faces, once ablaze with mountain fever, were now weary, anxious. We didn’t speak, but we knew what we had to do. Lifting ourselves from the frozen earth, we brushed off the frost and shouldered our backpacks. We fastened our jackets and cinched our hoods around our faces. And then, one by one, we ducked through the doorway and into the whirling whiteness. With luck we could make our way back to the village before night fell. I felt defeated, but I also felt we had no choice but to return. ▪

What came next? A story of Karma

As it turned out, Mike Schauch’s mountain did have a name: Mount Chako. And it had been climbed—once—by a Japanese party. A Bulgarian team also tried, but gave up when one of their group fell off a ridge and died. After his attempt, Schauch returned to the village, exhausted and bitterly disappointed. “At that point my whole reason for being was to climb that mountain,” he says. Now he felt lost. Why was he even in Nepal? he wondered. He soon found out.

As it turned out, Mike Schauch’s mountain did have a name: Mount Chako. And it had been climbed—once—by a Japanese party. A Bulgarian team also tried, but gave up when one of their group fell off a ridge and died. After his attempt, Schauch returned to the village, exhausted and bitterly disappointed. “At that point my whole reason for being was to climb that mountain,” he says. Now he felt lost. Why was he even in Nepal? he wondered. He soon found out.

The Schauchs wanted to know more. At a small school they found kids as young as three and as old as eight in a single classroom. Up front was a bright seven-year-old girl named Karma teaching English numbers. That night, Karma and her friends visited the Schauchs camp. All of them asked for chocolate, except Karma. She wanted the Schauchs to teach her more English.

“That day really sparked something in us,” recalls Schauch. Afterward, he and his wife visited with Karma’s family. They wanted to help and eventually arranged to pay for Karma and her sister, Pemba, to attend school in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital and largest city. That school, the Shree Mangal Dvip Boarding School, provides education to children from remote villages in northern Nepal. Eventually the Schauchs sponsored Karma’s other sister and have become host parents to two more Nepali girls from similar backgrounds.

In 2015, a massive earthquake struck Kathmandu, killing some 9,000 and injuring thousands more. Many buildings were destroyed, and Karma’s school was damaged. Once again, the Schauchs pitched in, helping organize fundraising efforts to rebuild. They’ve continued to support the school and formed a strong bond with Karma, her sisters and the other students they sponsor. Schauch’s book, A Story of Karma, tells that story, along with his experiences in the Nar Phu Valley and, of course, his fascination with a mountain that he never did climb.

What does Schauch hope readers take away from his book? “The ability to step outside of ourselves, have empathy for others and listen to others,” he says. “That’s how we break down our own personal biases and, in the process, get to know ourselves a lot better.” He pauses, then adds: “I think that’s a very important thing in context of our world today.”

Excerpt from A Story of Karma: Finding Love and Truth in the Lost Valley of the Himalaya by Michael Schauch. Copyright 2020. Rocky Mountain Books. All rights reserved. michaelschauch.com