Decoding Leadership Research

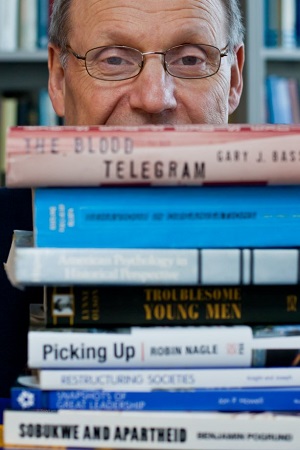

If there’s a recent research study on leadership that hasn’t landed on Julian Barling’s cluttered desk, it’s just a matter of time before it does. Yet he’s the first to admit that, when it comes to academic studies on the topic, “no one else would want to read them, given how dense they can be.” So he’s written a book, The Science of Leadership: Lessons from Research for Organizational Leaders, to demystify the research on leadership, and make the knowledge gained from it accessible to a wider audience.

There’s likely no one better qualified to take on the task. The school’s Borden Chair of Leadership, Queen’s Research Chair, and Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada has also been awarded fellowships in several other international organizations. There are no more prestigious academic appointments than these. He reads hundreds of research studies on leadership each year and has contributed a wealth of his own papers on the subject. He earned a PhD in psychology from University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, has received many major research grants and awards, including the National Post’s Leaders in Business Education Award in 2002, and has also been on the editorial boards of some of the leading academic journals in organizational behaviour.

The book has been a labour of love, he says. “It tries to convey what we know from behavioural science research on leadership in a way that is accessible and interesting to curious and motivated leaders,” Julian explains. “It’s designed not to terrify them with all these awesome theories, but rather to have the opposite effect. It shows that what we’ve learned from all this research on leadership is doable; that practicing leaders can do it, and can make a difference.”

Early reviews have been positive. Says Timothy Judge, Franklin D. Schurz Chair at the University of Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business, “Too often, researchers can get lost in the pursuit of innovation, and overlook the beauty of the hallmark studies that established the discipline. The Science of Leadership contains a wonderful balance of ‘old’ and ‘new’, blending the information seamlessly. It is a breath of fresh air on a subject that has long captured the imagination of researchers and practitioners alike.”

In advance of its January publication, Julian sat down with QSB Magazine to discuss the impetus for the book and some of the lessons he’s learned along the way.

What’s your fascination with the topic of leadership?

I’ve always been intrigued by leadership. As a child in apartheid South Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, I felt like I was growing up in a crucible. I witnessed first-hand the power of some leaders to cause incredible damage. Later, I watched the resistance to apartheid and how some leaders can bring about overwhelming good. So when it came time to decide on a major at university, psychology was the obvious choice for me. I’ve been fortunate to have been able to take what had always been a passion and turn it into my life’s work.

You’ve been studying and teaching leadership for decades. Why write a book for a general readership, instead of your usual academic audience, and why write it now?

The idea for this book came from teaching in the Executive MBA and Executive Education programs. I sensed a frustration that there were no really credible and accessible books that conveyed what we know about leadership, despite thousands of research studies. I realized there were non-academics who would like to know what the research has shown.

There are primarily two types of books on leadership: those written by academics for academics, and ‘pop’ books, those usually written by people with their own untested ideas about leadership. Although these ideas aren’t based on research, they sound catchy.

The fact that there’s a market for such books shows that there is a large group of curious, motivated, dedicated, ethical leaders out there who want to do good. Not just well, but good. There’s also a huge group of leaders who never get the opportunity to attend formal leadership training, and I hope that my book will speak to them.

One question you cover in your book that seems to resonate widely is whether leaders are born or made. Does your book provide a definitive answer?

For as long as people have had leaders, there have been opinions as to whether leaders are born or made. I devote a whole chapter of the book to this topic.

There is a widespread belief that leadership ability must be something some people are born with. Beliefs like this make psychological sense – when people are faced with behaviors that almost seem to defy explanation, as exhibited by wonderful leaders such as Mandela, or by the worst possible leaders, like Pol Pot, Stalin and Hitler, they need an answer. And in the face of the seemingly inexplicable, perhaps the simplest response is that it must be in their blood.

Fortunately, there’s research that can guide us in determining whether leaders are born or made. Studies in the 1960s showed that parents who used democratic child-rearing styles have children who were more democratic in their leadership behaviours with their peers. In the last 15 to 20 years, research studies have investigated family, parental, and non-parental influences on children’s leadership behaviours, and their findings, too, point to a significant nurturing effect.

Fortunately, there’s research that can guide us in determining whether leaders are born or made. Studies in the 1960s showed that parents who used democratic child-rearing styles have children who were more democratic in their leadership behaviours with their peers. In the last 15 to 20 years, research studies have investigated family, parental, and non-parental influences on children’s leadership behaviours, and their findings, too, point to a significant nurturing effect.

Most recently, we’ve seen studies that isolate the role of genetic factors in the emergence of leadership, that is, who becomes a leader in the first instance. There are some really interesting findings. For example, genetic factors explain about 30% of the variation in the emergence of leadership. That’s an interesting number, because it indicates that while genetic factors are important, much can still be done to influence who becomes a leader, and later, how people behave once they hold leadership positions.

The question that follows is: ‘Can leadership be taught?’ And the answer is a definitive ‘Yes!’ What the findings of hundreds of studies tell us is that leadership training can be effective, and cost-effective as well.

The great pity is that despite this, our operating model for leadership development in organizations across North America is dismal. I often ask the executives we work with, ‘Before or shortly after you were placed in a leadership position, were you offered any leadership training?’ And the answer overwhelmingly, is ’No.’ Training usually comes later, often much later.

We wouldn’t impose this model on any other important task in an organization. We don’t train surgeons after the fact. I’ve thought about this long and hard, and I can’t come up with one other occupation that sees a person being placed in a senior position, and only years later, offered relevant training.

Most frequently, then, there isn’t a model of leadership development in organizations; instead there are mechanisms for rewarding already successful and loyal leaders.

You devote an entire chapter of your book to gender differences, with an emphasis on ‘leader emergence’. What does the research tell us about gender issues and leadership?

A starting point is to look at the statistical data, and the numbers are discouraging at best. Only 4% of Fortune 500 CEOs are female; North American boards of directors have only 12-14% female representation; Canadian women Members of Parliament account for only 24% of the total number of MPs; the U.S. Senate has a 20% rate. In the year 2014, the most charitable interpretation is that a bias against women leaders persists.

We’ve also learned about a phenomenon called the ‘glass cliff’. When women do become leaders, it’s likely to be at troubled companies where the risk of failure is higher. In politics, studies show that women are more likely to be chosen to run in ridings which their party had lost the previous election and had little hope of capturing them in the next. We should not forget that Kim Campbell became Prime Minister when there was virtually no chance that her party could get re-elected.

But the big question is, ‘What can we do about this?’ One possibility is to look to countries where female representation on governance boards has been mandated, such as the Scandinavian countries, where women now hold 40% of board memberships. What’s interesting is that, after reaching the mandatory minimum, many companies voluntarily exceed that level. These companies recognize the value of having more women on their boards — the nature of problem-solving changes for the better, and women board members mentor other women, leading to an increase in their representation at the senior levels of the organization.

There is also evidence that we should start changing attitudes much earlier. A study reported a unique situation in India, in which some randomly selected local councils were directed to choose women as their leaders. Young girls who grew up with female role models had higher educational aspirations than girls without such examples. They also stayed in school longer, and were less likely to spend time on stereotypical ‘female’ tasks.

Clearly, we need to do more than just legislate female representation. Helping young girls grow up and see that positive leadership possibilities await them will likely have a very significant longer term impact, too.

Recently, you’ve tackled the concept of followership. A webinar you delivered (available at QSBInsight.ca) was entitled “Enough about Leadership, Let’s Talk About Followership!” What have you discovered about the dynamic between leaders and their followers?

Historically, researchers have studied leadership as if it’s a single-person phenomenon. Here’s a tongue-in-cheek analogy: imagine a therapist working on a troubled marriage, but choosing to interact with only one of the partners. I think we would all agree that would be ridiculous, but for decades, we studied leadership without including followers.

One study shows that looking at extroverted leadership by itself is no longer sufficient. You need to pair leaders’ extroversion with followers’ characteristics to really capture optimal leader effects on work performance. Pairing extroverted leaders with proactive followers resulted in poorer job performance! Performance was highest when extroverted leaders were paired with more passive followers, or when introverted leaders worked with proactive followers. Studying leadership in isolation from those being led is unlikely to tell the whole story. We need to stop thinking that leaders do everything by themselves. They don’t. Are they important? Yes, but there are more people in the picture than leaders alone.

Some earlier studies showed that follower performance dictates leadership style, not the other way around. For example, when follower performance declines suddenly, leadership behaviours become more controlling, with predictably negative outcomes. We have learned that it’s easier to be transformational when your followers are doing wonderfully.

After this promising beginning, research on this topic stopped. Not because we had the complete answer, I think, but because findings like these challenged our cherished beliefs about leadership. We have been raised to believe that leadership is not about responding to followers’ performance, but about causing their performance.

Challenging the potency of leadership raises difficult but important questions: For example, if followers are more important than we first thought, should we re-think executive compensation? Again, this is not to denigrate the role of leaders, it’s more about recognizing everyone’s contribution to the outcome.

The Science of Leadership is published by Oxford University Press. Julian will be speaking at events across Canada in early 2014 (details at qsb.ca/barlingbooktour).