The Little Car-Sharing Company that Could

Kevin McLaughlin hasn’t owned a car since 1990. Bought shortly after he graduated from Queen’s Commerce in 1989, the BMW 2002 was quickly sold after he returned from a life-altering trip he’d embarked on that autumn. Today, the founder and President of AutoShare gets around Toronto with his wife and two young sons by bicycle, on foot, or in a car from the company’s fleet of 300 vehicles.

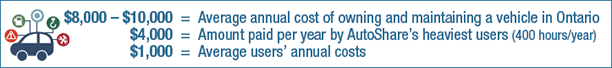

Kevin is one of 12,500 people who use AutoShare, Toronto’s first and only locally owned car-sharing company. He fits the profile of the typical customer: a resident of the downtown who doesn’t drive to work, has a postsecondary education, and is in the 20-to-50 age demographic (Kevin is 47). He deviates from the model in that his primary motivation is concern for the environment. For most of his customers, it’s all about convenience and saving money. They like the flexibility of reserving a car (by phone, online or via their mobile device), then using a smart card to access their vehicle of choice, from one of 175 lots, usually within a five- to ten-minute walk. The cost: a mere $10 per hour, including gas and insurance. It’s ideal for those needing to get to a late-night hockey practice, or for a trip to Ikea. For Kevin, it’s always been about the environment, but he’s learned to craft his message so that it resonates with a wide audience.

“We started off really focusing on the environmental side of things,” he explains. “Our corporate colours were green. Our message was, ‘it’s good for you and the environment’. Eventually, we realized that most people were seeing beyond that, and were looking at the convenience and cost savings. So, like that old TV commercial, we figured ‘if Mikey likes it, we’ll just tell him it tastes good’. We still have a very strong commitment to the environment. Hybrid vehicles make up 25 per cent of our fleet, and we’ve been pioneers in helping to bring electric cars into the city. First and foremost, though, we have to be a financially sustainable business.”

“We started off really focusing on the environmental side of things,” he explains. “Our corporate colours were green. Our message was, ‘it’s good for you and the environment’. Eventually, we realized that most people were seeing beyond that, and were looking at the convenience and cost savings. So, like that old TV commercial, we figured ‘if Mikey likes it, we’ll just tell him it tastes good’. We still have a very strong commitment to the environment. Hybrid vehicles make up 25 per cent of our fleet, and we’ve been pioneers in helping to bring electric cars into the city. First and foremost, though, we have to be a financially sustainable business.”

Kevin’s passion for environmental causes was sparked by an encounter with a “mountain of plastic water bottles stashed behind picturesque huts on a beach in Thailand,” he says. He came upon it during his postgraduation backpacking trip through Asia and Australia, and was troubled by the environmental implications. The 20th anniversary of Earth Day in 1990 fuelled media coverage and late-night discussions with his fellow young travellers. He’d left Canada anticipating that his journey would help him decide between a career in law or one in commercial real estate. Instead, he returned to Toronto later that year knowing that he wanted to work in the environmental field.

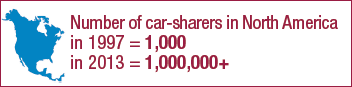

Local street artists created 250 unique parking signs as part of the company’s “Keys to Wonderful” campaign Subsequently, he met Geoff Cape (BA’89), with whom he would co-found the Evergreen Foundation, a non-profit focused on the environment. He moved to Vancouver to open the foundation’s office there and spent six years in the trenches, raising awareness and funds for a variety of initiatives focused on connecting people with nature in the city. The grind of the fundraising component took its toll, so when he heard that a new TV station was coming to Vancouver, he signed on as its first employee. He’d had high hopes of becoming a pioneering environmental reporter, and while some of his stories were picked up nationally, he found the TV-news business too competitive for his taste. He’d also been moonlighting as a co-founder of Vancouver’s Cooperative Auto Network (CAN), only the second such company in North America, modelled on Quebec’s pioneering Communauto.

Local street artists created 250 unique parking signs as part of the company’s “Keys to Wonderful” campaign Subsequently, he met Geoff Cape (BA’89), with whom he would co-found the Evergreen Foundation, a non-profit focused on the environment. He moved to Vancouver to open the foundation’s office there and spent six years in the trenches, raising awareness and funds for a variety of initiatives focused on connecting people with nature in the city. The grind of the fundraising component took its toll, so when he heard that a new TV station was coming to Vancouver, he signed on as its first employee. He’d had high hopes of becoming a pioneering environmental reporter, and while some of his stories were picked up nationally, he found the TV-news business too competitive for his taste. He’d also been moonlighting as a co-founder of Vancouver’s Cooperative Auto Network (CAN), only the second such company in North America, modelled on Quebec’s pioneering Communauto.

“It was very grassroots when we started,” he recalls. “We had to invent it as we went along.” Encouraged by the potential, Kevin decided that if it could work in Vancouver, Toronto might also be ripe for such a venture. “I had a network there and knew I could land at my parents’ place. I’d done well in investing in technology stocks in the ’90s, so I was able to return to Toronto with a bit of a nest egg.”

He found a partner and in late 1998, the pair launched AutoShare with two staff, three cars and 16 customers. “We started off working from our homes,” Kevin recalls. “Fairly soon, we realized the importance of finding office space. In a way, we were lucky to have launched AutoShare during a recession. The car-sharing business is somewhat out of synch with recessions, because when people are thinking about saving money, it’s good for us. It can be more difficult to get financing, but you can find and assemble a team of people more easily and cheaply, and office space is less expensive.”

He found a partner and in late 1998, the pair launched AutoShare with two staff, three cars and 16 customers. “We started off working from our homes,” Kevin recalls. “Fairly soon, we realized the importance of finding office space. In a way, we were lucky to have launched AutoShare during a recession. The car-sharing business is somewhat out of synch with recessions, because when people are thinking about saving money, it’s good for us. It can be more difficult to get financing, but you can find and assemble a team of people more easily and cheaply, and office space is less expensive.”

The two partners worked together for three and half years, then endured what Kevin calls “a messy business divorce.” After a lengthy litigation that took up most of 2002, Kevin was able to buy out his partner. “The company was more or less bankrupt when I bought it. I borrowed a lot of money to get it back on track, but it felt good to be able to run the business the way I felt it needed to be run.” The lesson learned, says Kevin, is to have a ‘shotgun clause’ — a mechanism to enable a partner to be bought out, or to buy out the other partner(s), using a pre-agreed compensation formula.

His Commerce background turned out to be invaluable in the early years. “Accounting was my least favourite course at school, but it turned out to be the most beneficial. Today, when I’m mentoring people wanting to start a business, I always tell them to take some accounting courses. I also say, ‘You’ll need a lot more money than you think. So apply for credit cards while you have a job, because you’re going to need access to all the capital that you can get.’ I’ve learned that when you start a business, it’s all in, and you need to get over many different humps to make it successful.”

The biggest hump Kevin faced at the beginning was explaining the car-sharing concept. “The analogy I’d use to explain the challenge was to say, ‘It’s not about getting them to choose Pepsi instead of Coke, it’s about answering the question, ‘What the heck is cola?’”

The biggest hump Kevin faced at the beginning was explaining the car-sharing concept. “The analogy I’d use to explain the challenge was to say, ‘It’s not about getting them to choose Pepsi instead of Coke, it’s about answering the question, ‘What the heck is cola?’”

It took a long time, but Kevin eventually drew on his past experience as a TV reporter to build the company’s reputation and solidify its legitimacy. “For the first eight to 10 years, a journalist at one of the big newspapers would ‘discover’ car-sharing and write an article about our great idea. A few months later, another journalist at a different paper would do the same. There are so many different angles to the AutoShare story — the environment, cost savings, start-ups and technology — there have always been new angles to cover.”

Kevin is a distant relative of auto-industry pioneer Sam McLaughlin, whose McLaughlin Motor Car Co. brought Buick to Canada, and merged with Chevrolet in 1919 to create General Motors

Kevin is a distant relative of auto-industry pioneer Sam McLaughlin, whose McLaughlin Motor Car Co. brought Buick to Canada, and merged with Chevrolet in 1919 to create General Motors

The evidence is plastered all over the company’s small meeting room, where new members used to sign up (today it’s all done online). Plaque-mounted news clippings from the National Post, The Globe, Toronto Star and many other media outlets cover the walls from floor to ceiling. “In the early days, we’d need a $500 deposit because our technology was such that we couldn’t bill customers for six to eight weeks, and we had to cover ourselves against bad debt. So I’d bring potential new customers into our meeting room and would explain how AutoShare worked. Then I’d come to the moment of truth, when they’d need to get out their credit card or cheque book. Initially, a lot people weren’t sure that we could manage the logistics of supply and demand to get them a car where and when they wanted it. So we filled the wall with media clippings. Every story helped legitimize AutoShare as being a real business. It allayed their fears that maybe we were running a Ponzi scheme, saying ‘Don’t worry – you’ll get a car’, when there were no cars to be had.”

Legitimacy isn’t an issue any more, but encroaching competition is. The little, local car-sharing company, with its staff of 25 and annual revenues of $6M, has now been joined by some major players; U.S.- based ZipCar, Avis, Budget and Daimler Mercedes-Benz have all entered the Toronto market. While Kevin isn’t quite putting out a welcome mat for these interlopers, he’s is confident that AutoShare will continue to thrive. “Word of mouth is big in our business,” Kevin explains. “Long before social media and smart phones, 50 per cent of our business came through word of mouth. When people would hear that a friend was using our services, it often convinced them that it was a legitimate and worthwhile choice. And their friends would often sell them on it, saying ‘Why renew your insurance? Why own a car? You should give this a try – it’s great.’”

While the company boasts customers from ages 21 to 81, the majority are young people in their late 20s and early thirties. “Our market research has shown that there are changes in life that trigger a decision to join AutoShare,” Kevin explains. “We seem to catch a lot of people in their late 20s, when they start having serious relationships, we think. They may not move in together, but they’re doing things with another person, getting a bit more serious, that’s when they decide to make a commitment to joining AutoShare.” Other triggers include a new job, a relationship break-up, or a move to a new apartment or condo.

While the company boasts customers from ages 21 to 81, the majority are young people in their late 20s and early thirties. “Our market research has shown that there are changes in life that trigger a decision to join AutoShare,” Kevin explains. “We seem to catch a lot of people in their late 20s, when they start having serious relationships, we think. They may not move in together, but they’re doing things with another person, getting a bit more serious, that’s when they decide to make a commitment to joining AutoShare.” Other triggers include a new job, a relationship break-up, or a move to a new apartment or condo.

“We have a solid fan base,” says Kevin. “A lot of our customers really do love the service. I like to think Autoshare does the best job in the city — that we’re the solution for people who thought that the choice was either owning a car or living life as a hermit. The reality is that now you can live a perfectly normal life without owning a car. In fact, you can be a lot happier and richer for it.”