How to build a better playground

No one in North America is more closely associated with the subject of reconnecting children to nature than California author Richard Louv. Louv’s book, Last Child in the Woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder, is the seminal work in this area. Published in 2005, it documented how children benefit from spending time in nature and triggered a movement in play and education by sounding an alarm about the harm done to kids’ physical and mental health and cognitive development by societal trends that keep them indoors.

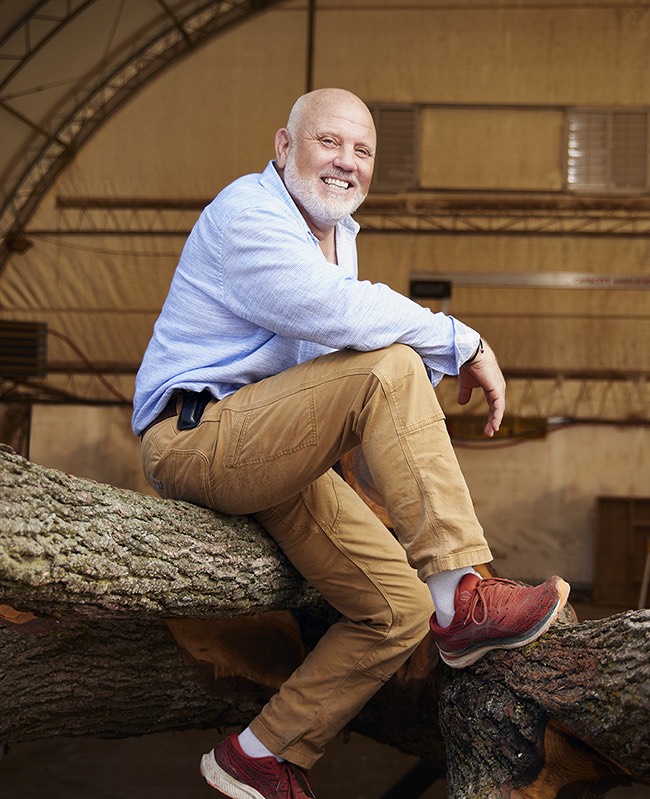

Given this, it isn’t a surprise to hear Louv’s name come up when I meet with Adam Bienenstock, founder of Bienenstock Natural Playgrounds, at his company’s main production shop on a rural highway near Hamilton, Ont.

Bienenstock, the company, is Canada’s foremost dedicated designer and builder of natural playgrounds, green schoolyards and outdoor classrooms — market niches that have seen dramatic growth in the past 20 years. Bienenstock, the man, as well as being a successful entrepreneur, is an international expert in natural playground design, children-nature engagement, collaborative project management and environmental advocacy.

Louv’s book came out around the time Bienenstock and his wife, Jill, an early childhood education specialist and the company’s director of education, were fine-tuning their business model. “Between that book and the moment that we knew we were having our kids, it all kind of gelled,” he says.

More surprising, though, is the story Louv tells me later, over the phone. It’s about Bienenstock’s impact at annual conferences hosted by the Children & Nature Network, a non-profit that Louv, now in his mid-70s, co-founded in 2006.

“Adam has been to several of those conferences. Often there’s 700 to 1,000 people there, but somehow many of them end up following Adam into the woods. I remember one time” — Louv laughs — “he comes rushing out of the woods with people behind him, and they’re covered with mud, and there’s mud on Adam’s face and body. And he was trying to get me muddy.

Bienenstock chats with children at Matilda Natural Playground in Hamilton, Ont. His company designed the playground, which sits on the site of a former gas station

“I didn’t want to play at that particular moment, I think because I had to speak right after that. But he’s been threatening ever since to get me into a mud puddle and finish the work. That’s kind of Adam’s spirit. He’s a big kid, which is wonderful. And what he’s doing is wonderful.”

Being called a “big kid” by your sector’s No. 1 thought leader is not something a lot of company builders would appreciate. But Bienenstock, while deeply serious about his work and mission, is not your average company builder. “I am the child in the room that needs to grow the heck up,” he says. “I think that play is the core. It is the secret to not aging. I think it is the secret to growing up properly. And I think it is the secret to bring community together, in the middle. It is the hook that we should all seek.”

In essence, the Bienenstock Natural Playgrounds story is a manifestation of this belief. Not just that kids need to play, but that it must be outdoors — in nature or in outdoor spaces that incorporate natural materials, have trees and shade as a respite from a changing climate, and offer the attendant levels of risk and challenge that come with those environments.

“When we started, every plastic and steel and post and platform and rubber manufacturer told us that what we did was illegal and what we did was going to injure kids,” says Bienenstock. “There was no question in my mind that we were right, and they were wrong. Now, every single one of them has a line [that’s] natural or inspired-by-nature. That, to me, is progress.” This explains, in part, why Bienenstock describes his company as a “social entrepreneurship.” Growing the business has also meant growing the movement ignited by Louv’s book — not only by designing and building natural playgrounds but also by making the case that they are healthy, safe and needed.

Hence, Bienenstock is a frequent speaker at conferences. He advises planners and landscape architects. He and his team engage with standards boards and insurance groups. “You can rail against [opposition], but it doesn’t get you anywhere,” Bienenstock says. What works is to “solve the problem.”

A case in point: To counter “fear-based decision-making,” he partnered with a handful of academics — including Ian Janssen, professor at Queen’s School of Kinesiology and Health Studies — to review the academic literature on the relationship between risky play and children’s health. Their paper, published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health in 2015, concluded that “the overall positive health effects of increased risky outdoor play provide greater benefit than the health effects associated with avoiding outdoor risky play.”

His business achievement metrics are similarly inspired. “We measure our success by having the kids be connected to nature, an authentic experience in nature. The money is a byproduct. On any given day, right now, 280,000 kids are playing on one of our spaces. The target’s a million.”

For the industry as a whole, he wants to see 30 per cent of the market consist of authentic natural spaces for kids. “When we started, it was like, ‘oh, zero-point-zero-whatever.’ Now I’d say it’s a healthy seven to eight per cent.”

Touring the company yard, wearing a ball cap, a faded black t-shirt, khakis and bright orange running shoes, Bienenstock is in his element. The site is alive with the sound of hammering and power tools. Loaders and log handlers rumble over wet, muddy gravel. Employees we meet say hi and share a laugh.

There’s nothing complicated about the 3.5 acre site. There’s a modestly decorated mobile trailer office at the front, workshop bays in the middle, stacks of raw timber at the back and an array of stump stools, wooden bridges, elaborate log structures and other finished pieces on skids on the perimeter.

“On every single piece that goes out, you will always see the real log,” Bienenstock says. That’s part of what makes it a “natural” playground. He slaps his hand on a big trunk segment that’s part of a piece in progress. “When this thing’s installed, there’ll be a spot right here where kids will rub enough that you’ll see the mark from the sweat of the palm of their hand. That means that this had the effect we wanted. You converted a kid in that process to loving this thing.”

That aesthetic is just part of the Bienenstock formula, however. As Jill Bienenstock explains to me later, the structures and spaces they create are also nuanced, sophisticated designs attuned to the developmental, social and safety needs of children of all ages.

That can be small things, she says, like choosing the right type of shrubs and planting configurations so kids can “make it a living fort.” Or it can involve incorporating “graduated challenges” into climbing structures, “which means that the youngest can’t get to the very top because we don’t put a handhold there. So they will experience the component in a different way than an older child who can get to the top. Because if you can get to the top by yourself, then generally you can handle the fall.”

All told, the company has about 70 staff, a diverse mix of designers, planners, educators and builders, including four master chainsaw carvers. Its installation team is based at a second, larger site nearby, where they keep their trucks, trailers, bulldozers and other heavy equipment. That group services the regional Canadian market. In the U.S., Bienenstock has an office in Boulder, Colo., and project managers in other cities. It subcontracts installation and basic construction work there to local firms but will also send staff from Canada for things that require “serious expertise.”

Next stop for the pieces on skids is delivery to clients. “We do about four 53-foot tractor-trailer loads of finished product that leave here every week,” Bienenstock says. There’s no telling where they might end up. The list of Bienenstock clients and installation sites is as varied as its product line. To date, the company has completed more than 3,200 projects in Canada and the U.S. (along with a handful of consulting roles in Saudi Arabia, New Zealand, Australia and Indonesia). Most of these are at community centres, municipal parks, schools and preschools — including the elementary school that Bienenstock attended in the 1970s when he was growing up nearby in the town of Dundas, within the city of Hamilton, where he still lives today.

But along with those, Bienenstock’s client list includes other unique, large and/or illustrious clients such as Parks Canada, the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, the Ontario Science Centre, Zion National Park in Utah and the Cabbagetown Business Improvement Area in Toronto.

For the latter, in 2022, the company built the Cabbagetown Parkscape project, a summer-long installation of five parkettes featuring dirt, plants, natural benches, climbers and other Bienenstock creations on Parliament Street, a busy north-south corridor. Bienenstock says street sites and other pop-ups are opportunities to reach children and their parents in “unlikely” places.

The Zion National Park project, still in progress, is Bienenstock’s largest. He’s under contract to “design the children’s experiences” for the 19-acre site of the park’s new Discovery Center, a public-private collaboration on donated land just outside the 590-square-kilometre park. Other partners include Zion Mountain Ranch, the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah and the non-profit Zion Forever Project.

Bienenstock’s first link to the project was a referral from David Sobel, a leading American author and consultant in nature-based education for children. “They engaged me in working with the landscape designers and the facility designers to describe a lot of my work on developmental psychology and nature engagement,” says Sobel. “I said, ‘I can do the theoretical aspect of this, but if you want somebody who’s going to execute good designs, you’ve got to talk to Adam.’ ”

In a recent article, Natalie Britt, Zion Forever’s president and CEO, was quoted saying the space that Bienenstock creates “will set a national precedent for experiential and immersive learning — a place where children are going to be able to feel the freedom of climbing on a rock and getting their hands and feet in the dirt . . . We are going to get them away from the digital world [of] devices and the pressures of social media.”

Although Bienenstock’s playground company took shape in the digital age, its origins lie in a personal and professional journey that started even before he founded his first landscaping business straight out of high school in 1984.

An American, born in Boston, Bienenstock is the second of three children. His father was a Jewish Hungarian whose family fled to England during the Holocaust. There he went to medical school and met Adam’s mother, also a doctor. They married and had Adam’s brother, then his father got a post at Harvard and they moved to the U.S. Next it was Buffalo, where Adam’s sister was born. Then, rather than be drafted into the army during the Vietnam War, his father chose to leave the U.S., landing at McMaster University in Hamilton.

“My formative years, between nine or 10 and 17, were all in Dundas, which is a world biosphere reserve,” Bienenstock says. “The [Niagara] Escarpment is this place that has rare salamanders and frogs and these weird junipers that are 400 years old. My childhood was steeped in all of that.” His path was also shaped by being dyslexic. So, while his brother and sister got scholarships to Oxford and Cambridge, he became “a really, really good landscaper and horticulturist.”

A decade in, he decided to up his game. He studied natural landscape design at the English Gardening School, then horticulture at Capilano University in Vancouver. “I was building very expensive gardens for very rich people, where my personal judge of success [was being] published in coffee table magazines,” he says.

At the time, he was also doing “school ground greening” on the side, “but it was never full time and it was never a recognized thing that had value.” At one point, Bienenstock recalls, a client asked him to do a playground privately. “I drew it, it was a stream, it had stumps lying across it and a little ropey thing that went over the gully. And they kind of patted me on the head and said, ‘That’s nice, but we asked for a playground.’ ”

Their response did not dissuade him. “How can you not see that that’s better?” He laughs. “It’s so obviously better. You know, it has water and mud and it’s got balancing things and you’re going to fall off and get wet.”

A playground company still wasn’t in his plans when he enrolled in the Executive MBA program at Smith in 1999. But it and two other events in the same period helped pave the way.

The EMBA program was “transformative” in helping Bienenstock understand the big picture of running a company. “I’d been in business for years and years . . . it was like I knew most of the puzzle pieces, but I’d never seen the cover of the box. And that program showed me the cover on the box.”

The same year he graduated, he also began seeing Jill. They were acquaintances as kids but went their own way as young adults before reconnecting. They married in 2002.

Lastly, immediately after finishing his EMBA, Bienenstock took a position as national program manager at Evergreen, a Toronto environmental non-profit. There, he developed the original business concept for Evergreen Brickworks, now a massive community environmental centre at the site of a former brickyard and quarry on the floor of the Don Valley in the heart of Toronto, which had its grand opening in 2010.

A playground in Rio Grande Park in Alamosa, Colo. that was created by Bienenstock’s company for a local public farming co-op

At Evergreen, he also led initial development of the Native Plant Database (now managed by the Network of Nature) and was the designer and team lead for what was then a somewhat radical natural playground project at Toronto Metropolitan University. Bienenstock did other natural playground designs while at Evergreen, but none were built. “Every one of them [was] stamped not for construction. We couldn’t get the insurance, [the] perception of risk was still too high for the board to handle,” he recalls. He quickly grew frustrated trying to solve big environmental problems and execute his ideas within the confines of a non-profit. “They’re too slow, they can’t take the risks required.” In 2002, he went back to his own business full time, where “I can take those risks all day.”

Dundas Central Elementary School is a large, historic, two-storey, red brick building in a mature, leafy residential neighbourhood not far from the foot of the Niagara Escarpment. Its first segment was built in 1857, making it the second oldest school in Ontario.

Bienenstock brings me here after our tour of his shop to show me one of his company’s finished products. But it’s not just any installation. He attended this school, as did his two sons. His house is a few blocks away. The house he lived in when his family moved to Dundas is across the street.

We head from the parking lot towards a clump of trees on the edge of a grassy area that occupies the front third of the school lot. “All of this was asphalt, and it took us nine years of convincing the school board that we should be allowed to do this.”

Under the shady canopy, on a bed of wood chips, are 20 or 30 stump stools that could double as stepping stones. There are other trees clustered around the lot. Bienenstock points out some willows near the front. “All the stormwater from the site used to head to storm drains, now there are berms that direct it into that patch. That’s why the willows are thriving, because of how wet that is.”

Under another set of trees there are new plantings, a bench carved out of a big log and a framed outdoor blackboard. The latter were added earlier this summer, during the company’s annual “day of service.” The outdoor space works, Bienenstock says, because “the trees we planted over a decade ago have grown up big enough that you actually have proper shade in the space.”

We sit in another spot, and I ask Bienenstock, who is 57, what’s next. Earlier he said his focus is primarily on advocacy, strategic direction and major project design. But, while he still wears several hats, it’s clear his singular ambition is to influence action that connects nature and children, schools and communities on a bigger scale.

Last year, he ceded the CEO role to John El-Raheb, a 16-year company veteran. He’s also gradually sharing ownership of the business. Long-term employees who have become partners now hold 25 per cent of the company’s equity. It all gives him more time for the sort of conversations that now “interest” him. That could still involve larger projects, like Zion, but it also means working more with government and policymakers, as well as individuals in the private sector.

“I should be talking to, you know, billionaires who want to get things done and want to see change happen rapidly, who are interested in the environment and see connection to nature as an important part of that,” he says. “I should be involved in discussions with government, whether it be provincial or state or federal, so that they can start to understand how important it is to invest in outdoor education [and] how we scale planting more trees in these barren environments that our kids are learning in.”

Bienenstock nods at the trees and grass in the schoolyard before us. This is the “front line” he says.

“If we believe [being in nature is] important immunologically, developmentally, behaviourally, emotionally, from a resilience perspective, then we want those [natural] spaces when and where those kids play — in the school, or in the park or in their backyard. And if you go to places where the equity issue is there, they don’t have a backyard because they’re in an apartment. So it’s only the school [where] they’re going to have a shot.”