Computer error

It was in early January 2016 when Charles Buchanan first got a glimpse into the state of IT networks and services in the non-profit sector. At the time, Buchanan was the board chair of a large agency serving newcomers to Calgary, and the board was doing an organizational review of the agency. That included a look at its technological capabilities.

Buchanan, then an executive vice-president of sales and marketing at a fintech company, was not impressed by what he saw. “It was abysmal. It was just thrown together over the years. It was not planned. It was not supported. It was not safe. It was not efficient and not effective.”

Digging deeper, Buchanan learned that different agency departments had separately purchased the same software to manage client relationships. A year prior, they began paying thousands of dollars a month for a subscription to a case management tool that was never implemented. The agency was “getting taken advantage of,” Buchanan says.

Worse still, the agency had contracted a local IT management company to handle its technology services, paying close to $10,000 a month. For that, the company only sent a part-time employee to visit the office twice a week. In addition, Buchanan saw that the agency wasn’t seeing the full potential of its data. “They did not do any meaningful analysis with their data to make predictions or show how they were doing.” This impacted the agency’s ability to receive funding and donations.

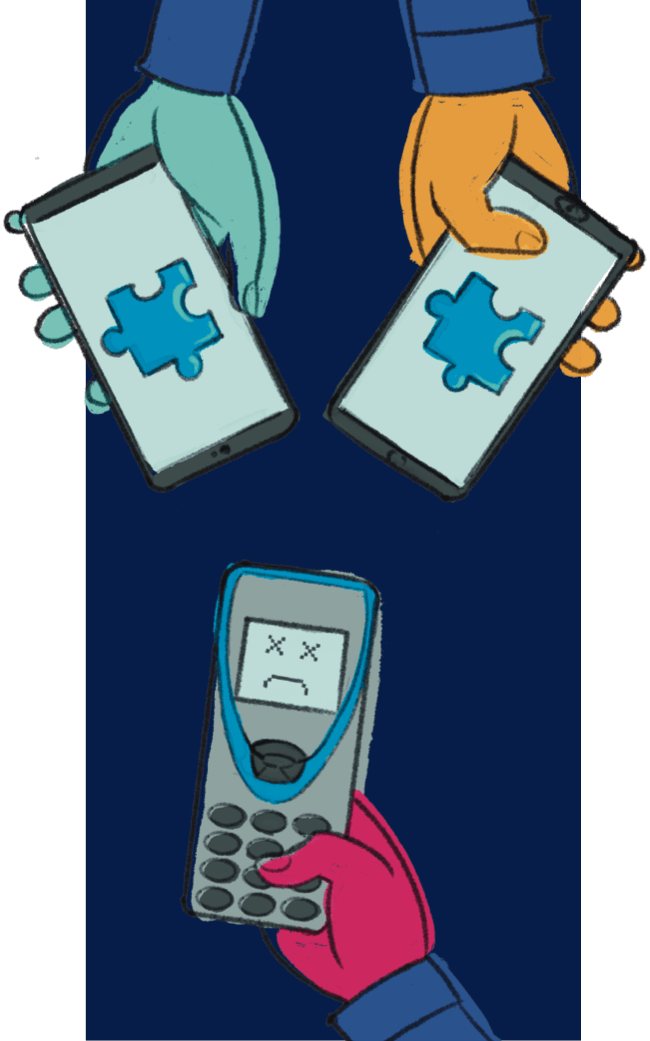

Digital divide

Pick a charity, any charity, and you’re likely to find a vastly under-resourced setup. That’s to be expected. Non-profits rely on donors who want their dollars to go directly to benefit the causes the charity pledges to support. That often means fewer employees and less than luxurious offices. Unfortunately, it can also mean a dismal jumble of technology. A 2021 CanadaHelps survey of 1,400 charities found that most believe digital adoption is important but 55 per cent say they either lack the funding or skills to do it.

The same survey found that 58 per cent of charities with less than $100,000 in annual revenue (that’s 50 per cent of all charities) have no plans to put digital into their everyday operations. In analogue times, that might have been OK. But no business can operate effectively today without proper tech. So how can non-profits function without?

That’s a question Buchanan asked after he visited the Calgary agency. Having spoken with board members at other non-profits, he had learned that poor technology systems at the newcomer agency were common among non-profits. “We saw one organization that had a washer, a dryer and a server all in the same room,” he says. These discoveries prompted Buchanan to start volunteering with charities as a technology adviser. But the need was overwhelming and he wanted to do more.

So, in April 2016, he quit his fintech VP job and launched Technology Helps. It’s a social enterprise that provides cybersecurity and support for social good organizations such as charities, non-profits, co-ops, social enterprises and underrepresented groups. He quickly landed his first client and, today, Technology Helps has a team of 20 that has assisted over 200 agencies with IT support—allowing them to better serve clients, save money and generate compelling reports for donors.

“We have to start seeing these organizations differently. We have to believe we’re investing in competent management and people”

“Someone starting their first job in non-profits said that our technology setup was way better than they had at their corporate job,” Buchanan notes. But he believes that non-profits with superior computer systems and support should be the standard, not the exception. “These organizations are on the frontlines doing hard, important work,” he says. “They deserve to have great services. These are the organizations that are keeping us safe. They’re educating kids. They’re helping vulnerable people.”

Finding a fix

So what needs to happen to equip more non-profits with the right digital-age technology? One change Buchanan wants to see: longer-term funding for non-profits. A lot of funding cycles are for one year, he explains. “That means agencies live year-to-year, applying to foundations to get funding and continue doing their work. They don’t know if they can serve their community in the same way if their funding gets cut,” he says. That makes it difficult for non-profits to plan, including for investments in technology.

Charles Buchanan

Buchanan also advocates for a shift in the culture of how donors want their funds used. “When you donate to a charity, you want 100 per cent of that to go to what you call ‘the cause’,” he says. “You don’t want any of that to go to infrastructure and administration, which technology is a part of.” Buchanan wants funders and donors to view themselves as investors instead. “We have to start seeing these organizations differently,” he says. “We have to believe that we’re investing in management and competent people who are doing things for the benefit of the community.”

Another important point: better technology doesn’t just help non-profits; it helps their clients. When charities don’t have proper systems, their clients suffer. For example, language classes for immigrants: to get into such classes, newcomers are advised to register with multiple agencies to improve their chances of getting in. But, says Buchanan, agencies don’t often coordinate with one another. “Being in a new country, not speaking the language, and having to fill out forms and be asked the same questions over and over again, I can’t imagine the sheer frustration they feel.” Unified data systems within and between agencies would reduce the barriers immigrants face.

At the same time, charities often help their clients with technology. Smith professor Tina Dacin, who researches social entrepreneurship and innovation, has seen the impact that inferior technology can have on people in need. “You might have four kids at home, but one computer is shared amongst the whole family,” Dacin explains. She says that charities can play an important role not only in getting technology to people who need it but also in instruction. “It’s a great opportunity for community organizations to come in and hold classes to bring people up to speed,” she says. Without having proper technology themselves, the assistance that these organizations can provide to vulnerable groups suffers.

Donor support

Buchanan is hopeful that donors are starting to understand how vital technology is for non-profits. He shares the example of a charity given funding to implement new software, but no money for the monthly subscription needed to use it. “We were firmly behind them declining the funding because that money would be wasted,” Buchanan says, likening it to giving someone a car without providing them with the means to buy gas. The good news: the funding organization re-evaluated the grant and gave money to support the ongoing maintenance of the new software.

Buchanan also cites the Northpine Foundation, a philanthropic organization in Toronto that offers multi-year funding to groups it supports. It’s an outlier from the standard yearly model. Buchanan hopes that a cultural perspective shift will provide a much-needed update to the way charities are viewed.

“Many social agencies are technology companies that offer a social service, as opposed to a social service that uses technology because they’re 100 per cent tech,” he says. “We need to recognize that the world has changed.”