Scott Lyall, BCom'87

There’s probably a high school art teacher out there shaking his or her head in disbelief at the thought of former student Scott Lyall being listed in Canadian Art magazine’s top ten artists. As the contemporary artist represented by galleries in New York, Paris, London and his native Toronto recalls, “I think I’d dropped art by grade ten.”

Scott Lyall He waited until his fourth year in Comm’87 to pick it up again when he enrolled in two art classes. Whether it was an unconscious picking up of a dropped thread or just a whim, Scott doesn’t recall. He does remember this: “I took a 100-level Art History lecture course and an open studio for drawing and sculpture.” Still, he was not yet ready to dive fully into art. Law school at the University of Toronto beckoned first. His foray into the legal field, however, turned out to be a detour. His interest in art was rekindled when he spent a summer working in London, England, for Merrill Lynch. “I went to exhibitions at the Tate and Saatchi galleries and started buying art magazines,” explains Scott. “Although I did return to complete law school after that summer, I knew I would go to art school next.”

Scott Lyall He waited until his fourth year in Comm’87 to pick it up again when he enrolled in two art classes. Whether it was an unconscious picking up of a dropped thread or just a whim, Scott doesn’t recall. He does remember this: “I took a 100-level Art History lecture course and an open studio for drawing and sculpture.” Still, he was not yet ready to dive fully into art. Law school at the University of Toronto beckoned first. His foray into the legal field, however, turned out to be a detour. His interest in art was rekindled when he spent a summer working in London, England, for Merrill Lynch. “I went to exhibitions at the Tate and Saatchi galleries and started buying art magazines,” explains Scott. “Although I did return to complete law school after that summer, I knew I would go to art school next.”

When he finally did apply to several Fine Arts programs, he requested advanced standing. “I hoped my degrees would let me bypass the foundations year,” says Scott. They did. But he never expected to jump right into a Master’s program, especially at one of the top art schools in the US, the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). “I think my Commerce degree contributed to the critical-thinking skills that enabled me to think and talk conceptually about art, which,” he reflects, “is what CalArts was all about in the ‘90s.”

It was an intense experience for Scott. “Art presented challenges that were huge for me. I didn’t know the people in art; I had to learn how to map a career in a whole new social situation. Also, I had to figure out how to make things, how to operate my own hands. I like those kinds of problems.”

Isaac Applebaum, Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery He found that lessons learned through both his business and legal studies contributed to his art practice. “The thinking that’s involved in commerce and law is useful because it tends to be task oriented and organizational.” Scott’s work – whether paintings, sculptures or assemblages of both – relies primarily on organizing experiential qualities, such as the colour, shape, dimension and scale of images and objects. “When I start a project, I usually begin with a formal and physical problem rather than imposing conceptual language and a narrative theme. I almost always begin on screen with a computer design process. From there, I output the screen images into material – print-out, dye sublimation (inked fabric), laser-cut building material and so on.” He then assembles the objects into compositions – or “scenes”– in the exhibition space.

Isaac Applebaum, Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery He found that lessons learned through both his business and legal studies contributed to his art practice. “The thinking that’s involved in commerce and law is useful because it tends to be task oriented and organizational.” Scott’s work – whether paintings, sculptures or assemblages of both – relies primarily on organizing experiential qualities, such as the colour, shape, dimension and scale of images and objects. “When I start a project, I usually begin with a formal and physical problem rather than imposing conceptual language and a narrative theme. I almost always begin on screen with a computer design process. From there, I output the screen images into material – print-out, dye sublimation (inked fabric), laser-cut building material and so on.” He then assembles the objects into compositions – or “scenes”– in the exhibition space.

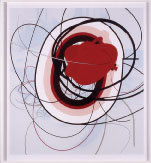

A Single Man Acrylic paint, ink, pen ink and graphite on printed paper Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid, Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery

A Single Man Acrylic paint, ink, pen ink and graphite on printed paper Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid, Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery

“I have more faith in the art market than in state-sponsored grant systems.”

Scott describes this process as “sceneography,” a term from theatre that describes the development of visual aspects such as set design and stage spacing. “It’s a term used more and more by museums to talk about the theatrical side of staging exhibitions,” he explains.

Against the odds, especially for experimental and conceptual art, Scott’s work sells. “I haven’t had to take any grants,” he admits. “Though I’m based in Toronto, I work a lot in the US, which helps. People buy art there. But I also make the work with the idea that the elements in the show can be sold as stand-alone objects after the show is over. It’s an important consideration. I have more faith in the art market than in state-sponsored grant systems.”

Several large collections have purchased multiple parts, even whole shows, including the Stone Foundation (San Francisco), Thea Westreich Art Advisory (New York) and the Francois Pinault Collection (Venice). “This is really the most exciting for me,” says Scott, whose works are regularly exhibited in galleries in New York (Miguel Abreu), in London and Paris (Sutton Lane) and in Toronto (Susan Hobbs). Isaac Applebaum, Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery

Isaac Applebaum, Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery

Against the odds, especially for experimental and conceptual art, Scott’s work sells.

Scott Lyall is living the dream. Although his rise in the art world may look easy in retrospect, he worked hard to build his career. “After I graduated from CalArts, I worked as a studio assistant for Dara Birnbaum, an appropriation artist working in video at that time. I lived in New York with a group of friends and plugged away at my own practice.

“In a way,” Scott muses, “art is about the way you live your life. It’s like a set of tools you develop to see how everything else is meaningful.”