Bearing Witness

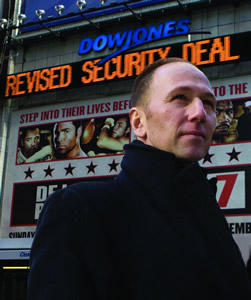

Bill Bamber, MBA’94, former Senior Managing Director at the eponymous Wall Street investment bank, is the co-author of Bear Trap: The Fall of Bear Stearns and the Panic of 2008. In an introduction penned exclusively for QSB Magazine, Bill provides the context for the book excerpt that follows.

It all started with a little rumour on an otherwise relatively ordinary Monday morning in early March. Just an off-handed comment about liquidity problems at Bear Stearns, the United States’ fifth-largest investment bank. And while the rumour wasn’t true – the firm had a reported $17 billion in cash-on-hand – it didn’t go away. The firm’s leaders at first remained reticent; they didn’t want to give any credence to these rumours by acknowledging their existence. But by Wednesday, the decision was made that someone needed to say something. By that time, it was too late. The damage was done. By Sunday, the firm was dead, absorbed by financial conglomerate JPMorgan for what most analysts said was as bargain-basement a price as they could have imagined.

It was, form any, an impossibly fast destruction of an 85-year-old Wall Street institution. In the space of seven days, Bear had gone from a financially solvent investment bank to a mere memory. The drama of its demise should have served as a cautionary tale to other Wall Street institutions. As the momentous events of September demonstrated – with the fall of Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual and the absorption of Merrill Lynch by Bank of America – other venerable firms failed to heed the warnings.

In the months since Bear’s collapse, a great deal of critical ink has been spilled to discuss and dissect the growing financial crisis. It seems that everybody has an opinion, with many from the financial world offering themselves up as experts on the subject. I’ve got an opinion on it, too. But I’m not one of the newly anointed experts.

I was a derivatives trader at Bear Stearns.

And now that I say that, at least in my own head it sounds like I’m introducing myself at a Twelve Step meeting. It’s an appropriate comparison, I think. After all, if you want to know about the misery of addiction, there’s no better person to tell you about it than another addict. To take the parallel to its obvious conclusion, if you want to learn what it was like during those horrible days behind the glass façade at 383 Madison Avenue, there’s probably no better source than a former Bear employee. At least that was the logic that drove me to pen Bear Trap: The Collapse of Bear Stearns and the Panic of 2008 (with co-author Andrew Spencer), released in September.

The excerpt that follows is the introduction to Bear Trap that sets the scene for the dramatic collapse of the storied Wall Street institution. For an academic’s view on the global financial crisis that followed fast on the heels of Bear Stearns’ demise, see ‘Fees and Leverage’ by Finance Professor Louis Gagnon, on page 16.

The excerpt that follows is the introduction to Bear Trap that sets the scene for the dramatic collapse of the storied Wall Street institution. For an academic’s view on the global financial crisis that followed fast on the heels of Bear Stearns’ demise, see ‘Fees and Leverage’ by Finance Professor Louis Gagnon, on page 16.

I didn’t always intend to write the story of Bear’s demise. I was actually in the process of writing a book on derivatives. It was to be a first-hand account of the nuances of the derivatives market – something that might appeal to students, maybe even students at Queen’s School of Business. But, to steal a line from Steven Sondheim, a funny thing happened on the way to the printer. The company for which I was working as head of derivative structuring – and, by association, the company that was serving as the basis for the content of the book I was writing – suddenly found itself at the centre of what can only be called a financial shit storm. So I did what any good trader would do in my position: I sought an alternative strategy that would allow me to profit from the market conditions.

John Colby, who was the publisher overseeing the derivatives book, introduced me to Andrew Spencer, a writer-cum-literary agent, and together we wrote the story of the death of Bear Stearns – a story I never dreamed I would write while I was but a student at Queen’s those seemingly many years ago.

Introduction: “How do you document real life when real life is getting more like fiction each day?” -Rent

Introduction: “How do you document real life when real life is getting more like fiction each day?” -Rent

You just can’t make this shit up.

I have no idea who deserves the credit for first coining that phrase, and I have to plead an equal level of ignorance when asked to identify the number of times it has been invoked over the course of human history to describe a given situation. But I do know, without the slightest shade of any sort of doubt, that there has never been amore appropriate description for a situation like the one I lived through beginning on Monday, March 10, 2008. So appropriate did I find the phrase, in fact, that it was the last thing I said to a co-worker, a friend who, because of the time he’d spent on a Navy attack sub, had acquired the nickname of Captain Nemo on the trading floor. And so perfect a summation of our situation was it that the phrase became something of a battle cry for the two of us as the days went by, a sort of inside joke that made the pain of our demise more bearable. And it started on Monday, March 10, 2008, the day that, in my mind, came to be known as the beginning of the end.

The day began innocently enough. I awoke, as was my custom, at five o’clock in the morning. I did the obligatory check of emails that had come in overnight on my BlackBerry – mostly a flurry of questions and concerns related to the overseas markets interspersed with a few offers to increase my manhood – and went for a morning run around my neighborhood and through Central Park. I showered, watched the early market reports on CNBC and got dressed. I was able to grab a quick espresso and bid goodbye to my family, and then I was out the door and on my way to the office on Madison Avenue. The only thing remarkable about the morning’s routine was the sheer lack of anything remarkable associated with it.

It Started On A Monday. By Sunday, An 85-Year-Old Wall Street Institution Was Dead

I usually opted for a taxi in the mornings, preferring the flexibility of hailing a cab to the rigid schedules required by New York car services. And what’s more, I worked at Bear Stearns, the company whose former CEO was notorious for the circulation of memos reminding us to save paper clips whenever we received documents from sources outside our office. It was, to his mind, a cost-cutting measure. So you could say I was baptized at the Church of Saving Money, and the ten-dollar cab ride was easier to rationalize, financially, than a car service. And I also managed to convince myself that it was a luxury when compared to the subway, so it made me feel pretty good all-around to take a cab. I made it to the office in about fifteen minutes, and I was at my place on the trading floor by seven-fifteen, ready for whatever the day might throw at me. Or so I thought.

What I loved most about my job was that it was always changing, never predictable, and I never knew what to expect during the course of any given day. Whereas a salesman knew he was going to be selling all day and a teacher knew he was going to be teaching all day, there was no discernible routine for me; my “typical” day was anything but typical. My specialty was structured equities, which means that I spent the day creating securities that have what you might call interesting payoff profiles. That’s Wall Street talk for “making rich people richer.” And despite the mundane-sounding nature of that job description, there was a very fluid nature to its dynamic, and I was constantly investigating new strategies and angles from which to approach issues. And yes, that means I was constantly trying to find ways to make the aforementioned rich people even richer. But today, Monday, March 10, 2008, was going to challenge both my views of what qualified as “anything but typical,” as well as my feelings towards that descriptor.

For those who have never actually been in the environment of the New York financial world, it often comes as a surprise that a trader’s “office” is actually a long desk on the trading floor, an open space that he might share with up to four hundred other human souls. It’s a far cry from what one might expect of the environs of that segment of humanity Tom Wolfe labeled “the Masters of the Universe.” At the table on the floor where I spent the better part of my waking life – one of four trading floors in the Bear Stearns New York headquarters – I was one of many crammed into a space designed for half our number. Each individual desk served as the work area for twelve people, six to a side. It’s something like a very crowded, very loud video game arcade, with video monitors and people everywhere. Or perhaps NASA Mission Control on a bad day. To those of us who work in these dwellings, it’s known as simply “The Desk.” It is the central nervous system of an investment bank and often serves as the place where we eat every meal of the day.

There is no such thing as privacy in this world. The phone bank at my place was linked into forty separate phone lines, and my coworkers could just as easily eavesdrop on any of my calls as I could on theirs. Successes and failures become public knowledge instantaneously in an environment such as this one. And rumours. Rumours run rampant in a place like this, like chicken pox in an elementary school. There’s no place for them to hide, and there’s no place to hide from them. As soon as I took my place at my spot on the trading floor, the rumour fire started, first as a spark, and soon grew into a full-on blaze.

My place within this technological sardine can faced directly into four separate computer monitors, each with a specific and equally vital purpose for my daily activities. And while financial information related to specific markets flashed across the various displays, it was my Bloomberg that was to become the object of increasingly intense focus as the day went on.

The Bloomberg machine, just “the Bloomberg” in market parlance, is as vital a piece of equipment for a trader at an investment bank as a hammer is for a contractor. It provides the user with, among other features, an amazing array of information about important news relating to specific companies and financial markets. On this morning, the specific company in question was Bear Stearns, the specific financial market was our own and the important news was bad.

Rumours Run Rampant ... Like Chicken Pox In An Elementary School

Words like “liquidity” were popping up on the Bloomberg, and those reports that were using the word were referencing a discernible lack of capital in the coffers of the company that had served as my employer for the last six years. But I didn’t put a whole lot of faith in these rumours, because that’s all they were. Rumours. Vicious rumours. Bear Stearns had always had the reputation of being a maverick in the world of investment banking. This was, no doubt, just another attempt by some jealous rival to bring us down. Investment bankers could be downright petty when they wanted to be.

Words like “liquidity” were popping up on the Bloomberg, and those reports that were using the word were referencing a discernible lack of capital in the coffers of the company that had served as my employer for the last six years. But I didn’t put a whole lot of faith in these rumours, because that’s all they were. Rumours. Vicious rumours. Bear Stearns had always had the reputation of being a maverick in the world of investment banking. This was, no doubt, just another attempt by some jealous rival to bring us down. Investment bankers could be downright petty when they wanted to be.

Yes, we’d gotten stung the summer before, when the subprime mortgage crisis made financial headlines and two of the firm’s hedge funds had collapsed. But we’d recovered. Our Chief Financial Officer told us – hell, he told the whole world – that we were doing fine as recently as February: “Our capital position is strong,” Sam Molinaro had told our investors in a conference call whose transcript had been strategically circulated to every major news outlet in the country. He said that our balance sheet showed financial improvement and that we’d cut our risk level across the board.

Nowhere in any of those reports was there anything about liquidity, insolvency or bankruptcy. And while perhaps I was being naively fed – and equally naively eating – the party line being offered by the hands of a bunch of spooked corporate executives, there was nothing that I could see from my vantage point that gave any credence to these rumours. So I went about my day, trying to block out the distractions.

But those rumours kept coming and those distractions became harder and harder to ignore. The higher-ups within the company made it a policy not to comment on rumours because they were of the strict belief that commenting on rumours did nothing but give substance to them. And rumours about investors panicking and withdrawing money in massive amounts due to a lack of money within the firm wasn’t one you wanted to give any kind of credence to. The rumours basically feed themselves, the conventional wisdom dictates, and once someone within the company has uttered the words, suddenly the rumours gain traction and begin to grow.

But after hours of cable television talking heads announcing to their viewers that Bear Stearns was on the verge of financial collapse, our executives broke with tradition and issued a statement. “There is absolutely no truth to the liquidity problems that circulated today in the market,” the release said at the close of trading Monday. And the Bear Stearns treasury department backed up the rhetoric with numbers. We were showing $17 billion in cash-on-hand. That’s billion with a b. To top that off, the firm’s balance sheets showed $11.1 billion in tangible equity capital and $395 billion in assets. In the world of investment banking, that’s sitting right on top of the mythical catbird seat. In other words, liquidity problems within the safe confines of the Bear Stearns universe were the punch line for jokes about other firms.

Of course, none of us were privy to the fact that the firm had been turned down for a $2 billion loan the Friday before. Declined. There’s no nice way to say it, sir, but your credit card was refused. And I know that a couple of billion dollars is not the sort of loan you typically walk into a bank and ask for. But in the world of über-high finance, this was an everyday thing that should have been an open-and-shut deal. A $2 billion loan is pocket change for these people, the kind of money you give the homeless guy on the street so your girlfriend thinks you’re a humanitarian. We were Bear Stearns, for God’s sake, the fifth largest investment bank in the country. Asking for and subsequently being approved for a loan of that amount is commonplace in the circles that people like us lived and associated within. It ceased being so commonplace, however, when we were denied the loan.

But none of us on our trading floor knew anything about it on that Monday.

So instead of worrying about things like non approved loans for our company, we slogged through the day in our blissful ignorance, deflecting these nasty rumours about our beloved firm’s balance sheets and credit worthiness. I did notice that I was spending more time than usual calming the nerves of jittery counterparties and investors who were calling with their concerns in regards to these unfounded stories, but all in all, the rumours weren’t causing too much damage. It never ceased to amaze me that well-educated people who trusted us with millions of dollars each were so easily influenced by the mere suggestion of trouble. One little pebble slips from the mountaintop, and suddenly all of Park Avenue is a-twitter with nerves about an impending avalanche. Fortunately for all of us, though, the news of the day took a sudden detour, knocking the Bear Stearns problems off the top of the news networks’ radars.

Our salvation came in the form of a 22-year-old Madonna, of sorts, in a story broken by the New York Times.

Her name was Ashley Alexandra Dupré, also known as Kristen. She was a call girl for the Emperor’s Club VIP escort service in New York City. In and of itself, the existence of an attractive twenty-something plying her trade as a member of the world’s oldest profession serving the white collar executives of Manhattan wasn’t necessarily front-page worthy. She lived modestly in a walk-up in the Flatiron District and counted among her career aspirations that of becoming a singer. Again, nothing Earth-shattering. But when the authorities busted the prostitution ring and made public the client list, “Client 9” turned out to be none other than the Governor of New York, Eliot Spitzer. Spitzer’s five-grand-an-hour dalliances overtook Bear Stearns’ financial problems as the scandal de l’heure. Apparently sex sells more papers than financial ruin. While I felt like I should have been mortified by the fact that the general American reading public was more concerned about yet another politician getting caught with his hand in the cookie jar than with the equivalent of all-out financial Armageddon on Wall Street, I was relieved that we were, at least temporarily, less newsworthy. God bless America.

People have asked me if I saw it coming. If I knew, somewhere in my inner-most soul of souls, that these rumours had not only substance, but arms, legs, feet and hands. That these rumours were much more than fantastic stories designed to bring down the Bear of Wall Street. And every time I’m asked, I answer the same. I didn’t know. I had no idea that the firm that had lured me away from another investment bank with the promise of a higher salary and more lucrative bonus structures in 2002 was on the verge of financial ruin in 2008. Perhaps it was some sort of deep-seated need to believe that the rumours weren’t true, some sort of inherent survival mechanism honed over millennia of DNA mutations within the genetic history of humanity.

A $2 Billion Loan Is Pocket Change For These People, The Kind Of Money You Give The Homeless Guy On The Street So Your Girlfriend Thinks You're A Humanitarian.

undefined If these rumours were true and Bear Stearns was about to be declared financially insolvent, the ramifications were potentially disastrous. If Bear Stearns went down, the rest of Wall Street was suddenly very, very vulnerable. And the results of that meltdown would be more disastrous than any financial panic in the history of the United States or the world at large. And to accept that possibility as reality was more than my brain could withstand at the moment. So I chose not to believe.

undefined If these rumours were true and Bear Stearns was about to be declared financially insolvent, the ramifications were potentially disastrous. If Bear Stearns went down, the rest of Wall Street was suddenly very, very vulnerable. And the results of that meltdown would be more disastrous than any financial panic in the history of the United States or the world at large. And to accept that possibility as reality was more than my brain could withstand at the moment. So I chose not to believe.

But Ashley saved us. Or at least distracted the world long enough for the rumours to be dispelled for another day. And there were other days. Lots of them. And as each of those days passed, more rumours surfaced. And as more rumours surfaced, some began to stick. It was like throwing spaghetti against the refrigerator. You keep throwing it long enough, eventually something sticks. And the more things began to stick, the bleaker the future looked for Bear Stearns. Our stock price plunged from over $80 a share to just over $2 a share in the course of a week. I personally lost several million dollars of my net worth. In the midst of my Bear stock losing approximately 97 percent of its value, it suddenly became harder and harder for my self preservation disbelief operation to function properly. But despite my own catastrophic losses, I considered myself lucky to have only lost the amount I did. There were thousands more just like me, and many of them had been far more invested in Bear stock than I, and thus lost even more. And it all started for us on Monday, March 10, 2008.

But this story, like all stories, has a beginning and an end, and Monday, March 10, 2008, was neither. It just happened to be the day that the horrific news of the all-too-real possibility of impending worldwide financial ruin was supplanted in the minds of Americans by the story of a twenty-two year-old hooker from the Jersey Shore who’d decided to make her fortune in the Big Apple, in part, by screwing the governor.

Like I said. You just can’t make this shit up.

Bear Trap is published by Brick Tower Press and is widely available at bookstores in Canada and the U.S. and online at Chapters.com and Amazon.com.