In Search of Good Governance

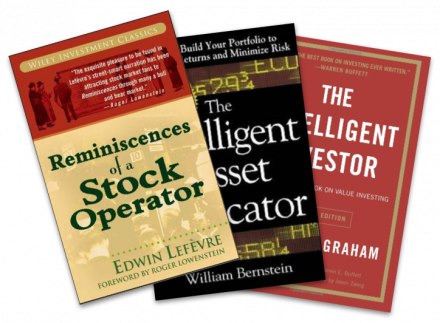

In Paul Calluzzo’s early years, the investment world was beguiling. Growing up on Long Island, N.Y., Paul (pictured right) watched as a Wall Street bond trader across the street grew wealthy and moved away to a posh neighbourhood. In high school, Paul’s favourite book was Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, the 1923 classic on the art of stock trading and speculation (see the “Professor's Library” on this page). In college, he was an intern at a finance firm and he bought his first shares — in Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Investing looked like a big poker game, with the smartest people owning the highest pile of chips.

That romantic view took on different — and more serious — shades as Paul did his PhD in finance at Rutgers University. His research focused on the role that human interaction plays in financial decision-making. It took him back to when he was a kid playing Monopoly, figuring out the best way to beat his brothers. “It’s just something I’m wired to think about,” he says. “This is the system and what are the holes that people try to exploit.”

Paul has pursued this question since arriving at Smith in 2014. As Assistant Professor of Finance, his research follows two intersecting storylines: mutual-fund performance and the influence of corporate governance on investments.

Contagions in the boardroom

Paul’s first studies looked at the sway of corporate executives who sit on mutual-fund boards. Starting in the early 2000s, mutual funds began to recruit executives from publicly traded firms to sit on their boards. Paul wondered, were these directors looking out for the best interests of the mutual-fund shareholders or their own interests? He painstakingly built a web-crawler algorithm that searched more than 130,000 mutual-fund filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and he collected by hand information about the employment history of fund directors. He also gathered data on governance quality of firms, using markers such as litigation records and shareholder rights.

Paul’s study showed that when mutual-fund boards have a public-firm director, “fund interests can shift away from shareholder interests and toward the director’s other interests.” For instance, funds held about 25 per cent larger stakes in the directors’ firms. Paul suggests that independent directors introduce either good or bad governance habits to mutual-fund boards depending on the experience with their own firms, a process he terms “governance contagion”.

As he settled in at Smith, Paul began to work with fellow researchers at the school. Together with Wei Wang, Associate Professor of Finance, and Serena Wu, Assistant Professor of Accounting, he looked at whether publicly traded firms operating on the outer edge of the law would leave town in favour of a location known for lax regulatory oversight.

Like crack investigators, the three professors triangulated corporate head-office relocations, firms that are more likely to come under scrutiny from SEC investigators, and the locations of SEC offices with a weak record of enforcement. The trio found that for firms likely to misreport activities or engage in earnings management, relocating headquarters was an attractive option.

“If you’re a child and you’re misbehaving, you don’t want to misbehave in front of your parents,” Paul reasons. “Our finding definitely aligns with what past research has shown: If you’re not behaving well, you don’t want to be around that monitor.”

About those anomalies

More recently, Paul teamed up with Smith finance faculty Fabio Moneta and Selim Topaloglu to look at whether institutional investors, such as hedge funds, trade on stock market anomalies. Anomalies are distortions in stock prices or rates of return that may be based on unfair competition, regulatory action, behavioural biases or events. If hedge-fund managers are as sophisticated as many believe, they should be aware of, and exploit, these anomalies to correct market mispricing. But evidence has yet to show that to be the case.

While the researchers didn't find a smoking gun, they did observe an increase in anomaly-based trading among institutional investors following the publication of academic research on the anomalies. In this way, the research Paul and his colleagues conduct contributes to more efficient markets. “We may not be saving lives but the behaviour of capital markets can have a huge impact on people’s well-being,” he says. “In the latest financial crisis, people bought assets that were mispriced and it ruined their retirement savings. We each make incremental contributions, and hopefully that makes the market function better.”

As for his early romance with investing, Paul says he used to think a slow and steady stock-picking strategy could beat the market. Now he believes typical investors lack the time and skills to outsmart Wall Street. But can investing still be rewarding? Yes, he says. “But I don’t believe you can outperform the market, and I do believe you can do stupid things if you’re not financially literate, or, for that matter, even if you are financially literate.” ▪

Smith Business Insight

Read more about faculty research at ssb.ca/insight