Safeguarding Pearson

While Ivan doesn't appear on the organization chart, he’s still an important member of the team led by Jennifer (Kooren) Sullivan, MBA’03, at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport.

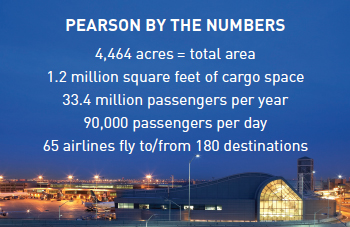

As General Manager of Safety and Security, Jennifer oversees a staff of 85 employees and hundreds of contractors whose shared responsibility is to maintain the safety and security of the facility and the 33.4 million passengers who pass through its doors each year.

Ivan is a bald eagle, and his role isn’t the only one omitted from the chart. Two dozen falcons and hawks, and the seven canine members of the unit are absent too, but all are equally important members of the larger team. Ivan and the falcons and hawks help keep the runways clear of birds, which can be lethal enemies of aircraft landing and taking off from any one of Pearson’s five runways. The dogs patrol the terminals, checking on unattended bags and vehicles and sniffing out suspicious substances, such as explosives. Their role, along with that of their human counterparts, is to safeguard Canada’s largest and busiest airport.

Pearson is owned and its workforce of 1,100 is managed by the not-for-profit Greater Toronto Airport Authority (GTAA). Its ambitious new mission is to become a global hub. What Frankfurt Airport is to Europe, Pearson intends to become for North America: the destination of choice for North American passengers making connections to the four corners of the globe.

As Jennifer and her team do their part to realize this global aspiration, one thing won’t change: her commitment to protecting the flying public and aviation staff. “People talk about the trade-off between offering good customer service and ensuring safety and security,” she says. “I come at it from a different perspective. I think keeping people safe is damn good customer service.”

For as long as she can remember, Jennifer wanted to be a pilot. She grew up in Toronto, close to the airport, and remembers visits with her father and brother to the parkade beside the old Terminal One building. “We’d stand at the railing at the edge of the roof for ages, watching the planes landing and taking off,” she reminisces. There was no single ‘aha’ moment; she just knew that she wanted to fly airplanes when she grew up. Not just any planes, but military aircraft, influenced perhaps by her father’s stint in the Dutch military before he immigrated to Canada.

A career in flight

As a U of T Political Science student in the late 1980s, Jennifer joined the Canadian Armed Forces Reserves. Her job in logistics at the nearby Downsview Squadron helped cover some of her expenses and served as her introduction to the military. Upon graduation, she applied to the regular Forces (Air) and was put through a battery of written and physical tests. One of the first ruled her out as pilot material because she wore glasses, but she made the grade as air crew, one of the few successful candidates in her group.

After boot camp (the “marching and saluting, no sleep and running drills” period), followed by French language and navigation training, she started flying on operational missions out of CFB Trenton in 1994 as a Navigator on CC130 Hercules transport aircraft. This was after the Berlin Wall had fallen and the Canadian Forces had shifted from Cold War readiness to peacekeeping and humanitarian missions around the world.

After boot camp (the “marching and saluting, no sleep and running drills” period), followed by French language and navigation training, she started flying on operational missions out of CFB Trenton in 1994 as a Navigator on CC130 Hercules transport aircraft. This was after the Berlin Wall had fallen and the Canadian Forces had shifted from Cold War readiness to peacekeeping and humanitarian missions around the world.

“It was a fascinating time,” she recalls fondly of her 15 years in the Forces.

She travelled around the world on missions to Bosnia, Haiti, East Timor, Kosovo and to several countries in Africa.

“A lot of people think of the military as being very regimented, with people marching around, saluting and saying ‘Yes Sir, No Sir,’ but it wasn’t like that at all,” she explains. “It was a dynamic and interesting job that gave me a lot of responsibility at a young age.”

She fell in love with Africa, visiting countries tourists wouldn’t dare to set foot in. One such visit left a lasting impression. Her crew had landed in the Central African Republic in support of a peacekeeping mission that was at risk due to the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Jennifer noticed crowds of young people outside the terminal entrance, all clustered beneath street lights. When she asked what they were doing there, she was told, “Oh, they’re just university students. They come here at night to study because this is the only place in town with electricity.” She hasn’t taken electricity for granted since.

September 11, 2001, was another memorable day of a completely different sort. She was about to leave on a training mission when images on the Trenton squadron’s TV showed a gaping hole in one of the World Trade Center’s towers. “The commentators were talking about an accident with a ‘small’ plane, and we were all saying, 'That was no small plane!' Later someone said, 'We know where we’ll be spending Christmas.' Sure enough, by November, our crew was flying missions to Afghanistan.”

Much as she loved her job in the military, Jennifer saw the writing on the wall when the advent of GPS and other new aviation technologies began diminishing the navigator’s role. In 2002, as a 36-year-old Captain, the contract that she’d signed on enrollment was about to expire. She could either commit to an additional extended period or take a buy-out and leave the Forces. Embarking on a second career in her 30s was preferable to starting over at 47 when she could retire with a pension, so she began exploring options in civilian life.

A Queen's MBA

“I realized I had all these great skills that I’d learned in the air force, but I knew the business community wasn’t looking for navigators. There are things you don’t do in the military—business planning, budgeting, marketing—and I realized I wouldn’t get far in business if I couldn’t read an annual report.”

Her partner of 17 years, Jim Sullivan—a former military fighter pilot, now with Air Canada—supported her pursuit of an MBA degree. Queen’s was chosen for several reasons: the requirement for work experience and the resultant older demographic, emphasis on team work, and the program’s 12-month duration. “I liked the intensive, jam-it-all-together and get ‘er done aspect,” she explains.“And of course, the Queen’s MBA reputation was unrivalled.”

Her MBA experience exceeded even her high expectations. “It was a really great transition from the military into the School and then out into the business world.” Professor Douglas Reid’s Strategy class left a particular impression, since he frequently touched on the aviation industry. “The economics of it are a disaster,” she laughs, “but there are those of us who can’t help ourselves because we love it. We know we could make a lot more money in plastics or widgets, but we’ve been bitten by the aviation bug.”

Friendships made during her MBA studies were lasting, with one couple, classmate Paul Arhanic and his wife Bree, becoming regular vacation mates. A 2010 sailing trip in the Caribbean included a stop at a beach where Jim and Jennifer had arranged to get married, surprising their sailing buddies in the process.

From YVR (Van) to YYZ (Tor) - a new career in civil aviation

It didn’t take long for Jennifer to find out if her MBA had been worth the investment. After graduation, she spotted an ad in the Globe and Mail for a position with the Vancouver Airport Authority. “Yes, I am that person who got hired through a Globe ad!” she laughs.

Jennifer and ‘her’ Herc, poised for take-off from El Gorah, Egypt, in 2000She had a whirlwind introduction to the world of civil aviation since the airport at that time was in a state of perpetual renovation and construction in advance of the 2010 Olympics. Of course, the Games themselves were a highlight, with athletes, officials, VIPs and visitors descending on Vancouver by the planeload.

Jennifer and ‘her’ Herc, poised for take-off from El Gorah, Egypt, in 2000She had a whirlwind introduction to the world of civil aviation since the airport at that time was in a state of perpetual renovation and construction in advance of the 2010 Olympics. Of course, the Games themselves were a highlight, with athletes, officials, VIPs and visitors descending on Vancouver by the planeload.

Jennifer and Jim led a jet-setting existence during her five years in Vancouver while Jim was based in Toronto. They commuted between the two cities, enjoying both. Just as their initial ‘let’s try this for five years’ plan was nearing its expiry date, a colleague at Pearson sent along a job posting for the GM of Safety and Security position. Here was a chance to move from an operation of 400 employees to Canada’s largest and busiest airport and all the opportunities that would entail.

Jennifer landed the job in 2010 and hasn’t had a dull day since. “My job is to ensure the safety and security of Toronto Pearson Airport, from the airfield fences and parkades to the terminals. Anything that happens on GTAA property involving the safety and security of people and their property is my team’s responsibility.”

Her team patrols the terminals and property and deals with hundreds of thousands of calls received annually by the airport’s operations centre. Reported issues run the gamut and include car accidents on road-ways and in the parkade, aircraft emergencies, unattended baggage and vehicles, medical issues, and licensing and policing airside vehicles such as fuel tankers and massive tractors that push back aircraft from departure gates.

Toronto Pearson’s Safety and Security Officers are another first line of defense against potential terrorist threats. This latter function carries unique challenges.

“It’s really hard to measure the things that don’t happen,” Jennifer muses.

“When you’re doing a really good job, everyone takes you for granted because nothing happens.”

Thanks to a proactive Wildlife Management Program, systems are in place to minimize the risk of ‘bad things’ happening—things like bird strikes that can cripple aircraft engines and deer that can wander onto runways. While the eagle, falcons and dogs keep wildlife at bay, a comprehensive habitat management program tackles the problem at its roots. The length of the grass between runways is maintained in accordance with the dislikes of migratory birds: When it’s nesting season, the grass is kept short so that birds are more visible and therefore at risk from predators. When it’s migrating season, the grass is kept long to deter them from landing to feed. Ponds fed by the run-off from runways are covered in netting to discourage waterfowl nesting and feeding.

One of the first things people think of when they hear ‘airport safety and security’ is an area over which Jennifer has no jurisdiction: the passenger screening process. This function is managed by the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA), the federal agency that staffs the airport’s 14 security checkpoints. Numerous surveys have shown that pre-flight security restrictions are the major ‘dissatisfiers’ of the flying public. While CATSA oversees the checkpoints, the GTAA team is responsible for a demand management system that enables screening points to be staffed in accordance with passenger volumes. Both groups work closely together to ensure the process runs as smoothly as possible, especially now that Pearson has set new standards governing the length of time it takes for passengers to make their connections. The current one-hour standard is being shaved to 45 minutes as part of Pearson’s mission to become a global hub.

One of the first things people think of when they hear ‘airport safety and security’ is an area over which Jennifer has no jurisdiction: the passenger screening process. This function is managed by the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA), the federal agency that staffs the airport’s 14 security checkpoints. Numerous surveys have shown that pre-flight security restrictions are the major ‘dissatisfiers’ of the flying public. While CATSA oversees the checkpoints, the GTAA team is responsible for a demand management system that enables screening points to be staffed in accordance with passenger volumes. Both groups work closely together to ensure the process runs as smoothly as possible, especially now that Pearson has set new standards governing the length of time it takes for passengers to make their connections. The current one-hour standard is being shaved to 45 minutes as part of Pearson’s mission to become a global hub.

“We’re competing for passengers far beyond our regional and even national base,” Jennifer explains. Of the 33.4 million passengers who use Pearson each year, 27% are actually connecting to other destinations. “We want passengers travelling from Los Angeles or Sao Paolo to choose Pearson for their connecting flights to Europe. Who wouldn’t choose a 45-minute layover in Pearson’s new terminal, with all its amenities, over a two-hour stopover at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport or the old and inefficient terminals at New York’s JFK?”

Unlike most air travelers, Jennifer makes a point of choosing flights that provide the longest connection times. She regularly visits other similar airports worldwide to keep tabs on best practices in her field. When doing so, she’ll choose two- and three-hour layovers, all the better to roam the terminals and take photos on her BlackBerry of things like eye-catching signage or corridor designs that improve passenger flow.

Now that nearly 11 years have passed since she left the military, she has no regrets. “I sometimes think that I’ve spent the last seven years protecting people from another 9/11. Meanwhile, my friends who are still in the military have spent the last ten years in Afghanistan preventing another 9/11. We all have the same objective, we’re just going about it from different directions.”