Turning the Tables on Bill Cannon

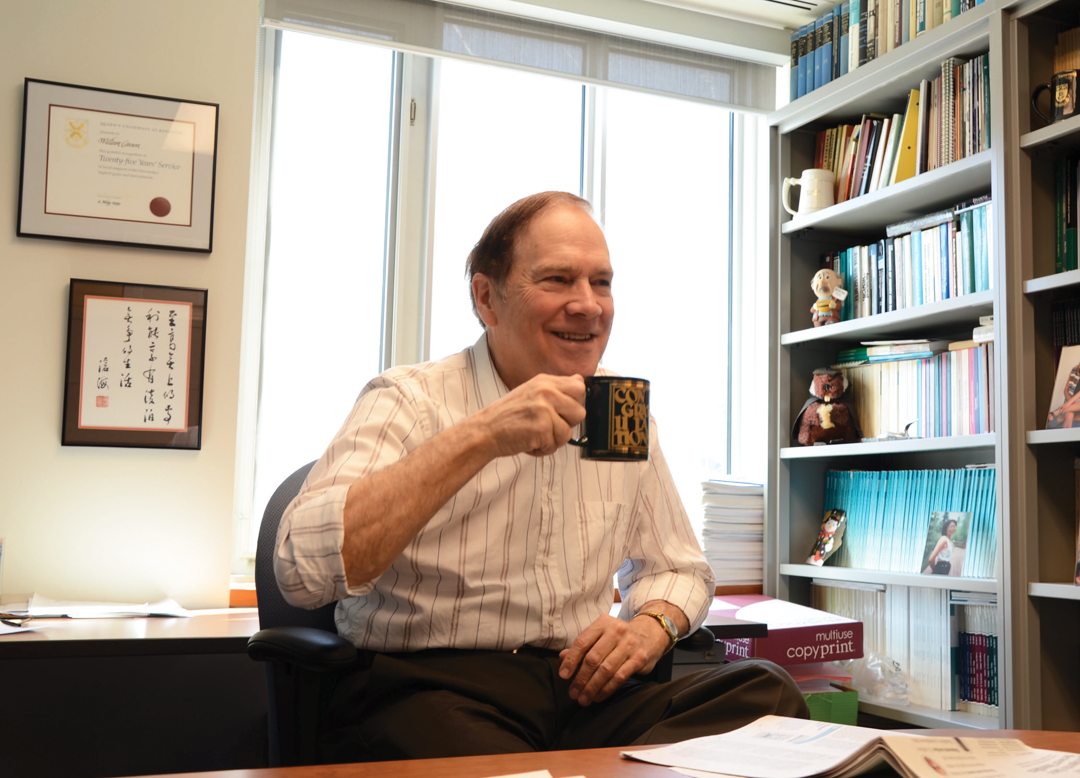

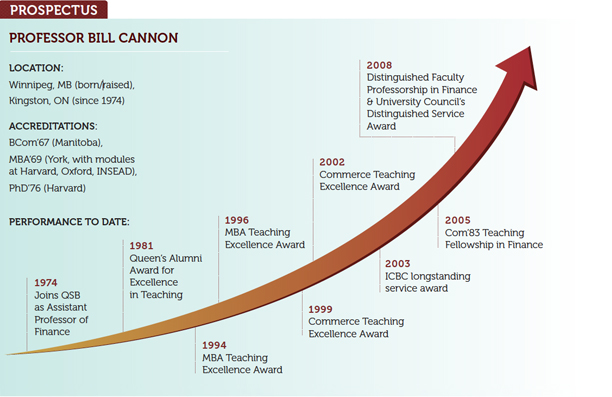

Usually, it’s the professors who get to ask the questions. In this first installment in a series of Faculty Q&As, QSB Magazine Editor Shelley Pleiter knocked on Professor Bill Cannon’s office door to pose some questions about what he’s taught—and learned—in his 38 years teaching Finance at Queen’s School of Business.

What stands out as a memory of your early teaching days?

I was a fresh PhD grad, very enthusiastic about my subject, and I felt that I had a wealth of material to impart to my students. I was excited to share it with them. I’d fill 12 legal-sized pages with my notes, then would just race through the material in class.

In retrospect, I realize I was asking the impossible. There was no way that the students could absorb it all. But one class I taught in my second year was very smart. Rather than moaning and complaining, the students chose one of their classmates to deliver a message. Angela Biever (BCom’75) came to my office and was extremely complimentary about my class. She told me how much the students appreciated my teaching efforts, how it was the best course they’d ever taken, and so on. After a few minutes of this, she had me eating out of her hand, and I swallowed her suggestion that everyone would learn even more if I would narrow the focus a bit and cut down on the volume of material.

I reduced my notes to about eight pages, and now I probably cover only three legal-sized pages. Just think of the thousands of students who benefited from this class’s tactic of catching more flies with honey than vinegar!

What do you hope your students remember from your courses?

What do you hope your students remember from your courses?

I hope they would remember always to keep their overall goals in mind. Whether just entering the business world, or later in their careers, or even in their personal lives, people should always be aware of the overall goals they’re trying to achieve through all their efforts.

In many situations people just assume that everybody knows what the goals are. That’s not always the case. In the business world, you need to know what your organization’s overall goals are and to be clear about how your actions and recommendations are going to link to the achievement of these goals.

This advice also applies to people’s personal lives. If you ask yourself, “Why am I working so late every night?” that can open up an internal conversation. “Because I want to make money. But why do I need to make more money when I already have enough? And by working late, I’m liable to lose my wife, and I won’t be able to help my kids.”

Instead of just getting locked into doing something because it made sense at one time, you need to keep asking, “Is what I’m doing consistent with what I ultimately want to achieve, or who I ultimately want to be?” As long as the answer is “yes,” you won’t make the big mistake of spending a lot of time on things that aren’t really helpful to achieving your ultimate goals.

What lesson from another professor has left a lasting impression on you?

When I was studying at Oxford as part of my MBA, I took a course taught by Sir John Hicks, one of the world’s foremost experts on Keynesian economics. We were in class one day in his huge office that was the size of one of the large classrooms at Goodes Hall. We were sitting cross-legged on this big Persian rug beneath a leaded glass window, listening to this learned gentleman who must have been in his eighties at that time.

He was talking about how monopolies can increase their revenue by restricting supply and maximizing price. Then he paused (and I could see that he was about to impart a pearl of wisdom) and said, “You all realize, of course, that the best of all monopoly profits is a quiet life.”

I interpreted this to mean that if you have some monopoly advantage—brainpower or energy or whatever—you can use it to become the head of an investment bank, and work 18-hour days to maximize profits. But if you’re smart, you’ll realize the best profits are a quiet life—having a family life, living to 90 or 100, not having a heart attack at age 50 because you’ve been working so hard.

It’s become a motto in my life. I’ve even had the phrase inscribed in Chinese calligraphy, framed and displayed in my office as a daily reminder of what’s important to me.

What lesson from your students has left a lasting impression on you?

I learned that what they really value is knowing that their professor is “on their side.” They appreciate when a faculty member is really committed to helping them achieve success in the course and in their careers. Sometimes, when we talk about things beyond the course work, the discussion turns to finding success and fulfillment in both their careers and personal lives.

They appreciate professors who are welcoming in their offices when students appear with questions after class. They don’t feel that the prof is the opposition or someone who’s trying to put obstacles in their way. Instead they value the professor who’s trying to break down obstacles and show them the best paths to achieve success.

What’s one thing your students likely say about you behind your back?

Well, I wouldn’t be surprised if it was something along the lines of, “I work so hard in Cannon’s course, I wish he would give me credit for my efforts rather than just my performance.” I explain every time that I have to grade based on what’s on their exams or in their papers. I often tell them, “I expect you to work hard, but if you are working hard and you’re not getting the grades, then either I’m explaining it badly or there’s some blockage.” Then I encourage them to come to my office and we’ll try to sort it out.

Well, I wouldn’t be surprised if it was something along the lines of, “I work so hard in Cannon’s course, I wish he would give me credit for my efforts rather than just my performance.” I explain every time that I have to grade based on what’s on their exams or in their papers. I often tell them, “I expect you to work hard, but if you are working hard and you’re not getting the grades, then either I’m explaining it badly or there’s some blockage.” Then I encourage them to come to my office and we’ll try to sort it out.

I often have students in my office and I regularly get emails from them, so they definitely take advantage of the offer to help them perform to the best of their abilities.

What’s next for you?

If I had been thinking about retirement before, I’m not now, thanks to a DVD my wife Tensia and I watched recently. It was about what retired men should do to keep healthy. According to a doctor in the video, there are three rules to follow:

- Keep reading in your field of interest.

- Get out of the house, get involved in the community.

- Associate with young people so you keep up with how the world is evolving.

I said to Tensia, “I’m already doing all those things— at work!” So it doesn’t make any sense for me to retire as long as the students still appreciate my efforts and the School still needs Finance professors.

I really love what I do, and I really love the students. It always picks me up when I’m around them, they’re such bright and talented individuals. Our job as faculty is to not misdirect them. They’re so motivated, all we have to do is point them and help them along their way, and they’ll be just fine.

On the cover page of my exams, I always write a personal message to my students. Over the last 30 years, it’s usually been, “Remember, when you have just missed your child’s birthday party or first gymnastics competition, and you are slaving away at your office past midnight for the fourth day in a row, trying to get out that pitch book on which you feel your $300,000/ year job hangs ... remember that you always have a choice, and some people believe that “the best of all monopoly profits is a quiet life.”