The Incredible Shrinking Marketer

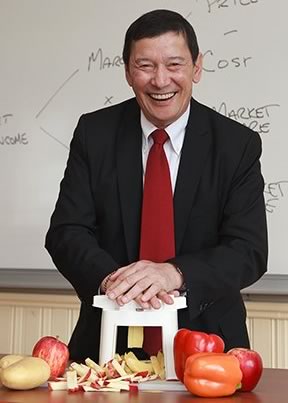

Ken Wong, QSB’s Distinguished Professor of Marketing, says it’s time to return to the roots of brand management in this white paper that originally appeared on QSBInsight.com. Its publication coincides with the 30th anniversary of his joining the QSB faculty.

Back in the 1970s when I started in marketing, I was introduced to what is now the standard framework used in virtually every introductory marketing course, the so-called four Ps: pricing, product, promotion, and place or distribution.

This framework was developed by Eugene McCarthy in the 1950s. McCarthy drew together all the decisions he thought any business had to make and grouped them under these four headings. It simplified the communication of his key message: that every marketing decision and action could not be made independently, that each one represented an extension or a manifestation of a business strategy, and that business strategy, when it was well conceived, should reflect the mission critical conditions required to satisfy a customer.

McCarthy’s intent was not to specify a template for the responsibilities of a marketing department or a chief marketing officer. These were decisions that could be made by anyone within an organization. All that mattered is that they were consistent in their focus on the customer. The framework worked and the brand management system was born.

The original brand management system violated one of the most basic management tenets that responsibility and authority should go hand in hand. Brand managers had responsibility for the bottom line performance of their business but no authority to force anyone to do anything. So brand managers had to understand what was happening in every other functional area, and then find a way of communicating to those other functional areas that doing what the brand manager wanted was not only in their best interest, but in the best interest of the organization.

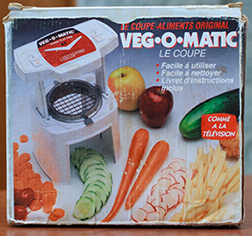

The system seemed to work beautifully. But it is not clear that it worked because it was a brilliant system or merely that the business environment at the time was benevolent. After World War Two, North American firms introduced a host of innovative products and because these products were new and consumers did not have experience in their use, the market was relatively homogeneous. We had the new communications technology of TV and there were a limited number of options.

These were brand new products, so life cycles were very long. There were no concentrations in the retail channels and largely fragmented distribution, so suppliers had the power in dealing with all channel members. Customers had no expectations and were happy with what they were getting.

Move forward the hands of time two decades. Markets exist in a state of hyper-segmentation, with markets of one. Consumers have more media choices than ever. Products have started to become commoditized: due to diminishing returns, there’s only so much durability, portability, or functional value you can possibly keep adding to a product and keep the costs reasonably low.

Private and controlled labels such as President’s Choice have now come to assume a major role in going up against national brands; they represent anywhere from 20 to 40 percent of some markets. Product life cycle? It’s not unusual, especially in sectors such as technology, for 50 to 65 percent of new products to be less than two years old.

We are now dealing with empowered consumers, people who want their products customized to their requirements and delivered where and when they need them most. This is a difficult environment in which to operate when you’re coming at it from a one-size-fits-all perspective.

We are now dealing with empowered consumers, people who want their products customized to their requirements and delivered where and when they need them most. This is a difficult environment in which to operate when you’re coming at it from a one-size-fits-all perspective.

Marketing hasn’t been dormant during this process. As new problems arose, marketers turned to technology and found any number of messiah solutions. We added a fifth ‘P’, proliferation. Suddenly, marketing was much more complex than at any previous time. Within the last five years, I have seen more change in the tools of marketing than at any previous time in my 35 years of marketing experience.

But with so much fragmentation in practice, the responsibilities for marketing activities have grown to be defused throughout the organization. In the absence of a strong general manager/brand manager, how could you maintain that central integrated focus? The answer was return on investment — ROI — the new metric. Suddenly, everything was now measured against financial contribution. The unity of the marketing effort drifted from a common focus on satisfying the customer to a common focus on satisfying the shareholder.

The logic was simple: if you’re making money and producing high ROI, you must be doing something right, or so we thought. What we failed to realize was that there was a better question to ask than whether or not marketing management was doing the right thing. In an environment of constant change, the real question was whether or not this existing model of marketing could sustain consistent performance within that environment. The answer to that question would seem to be a definitive no.

Part of the problem is the very nature of marketing and what a marketer now does. The Economist ran a survey in 2012 in which they asked CEOs to identify the responsibilities of their chief marketing officers. Of all the areas listed, there are only three in which marketing is given responsibility in 75 percent of all companies. What’s even more disturbing is to look at the areas where marketing is not considered to be a major player: pricing, new product and services, customer engagement, customer service, selecting new markets to enter, deciding new IT investments, and connecting customer-facing functions.

Organizations may want to spread the responsibility for making these decisions but it would seem to me that if a decision or a function has something to do with the customer, it should fall within marketing’s purview.

Why have these activities been taken away from marketing? Partly because of trust. When we asked CEOs how effective their organization’s CMO was — in broad areas such as establishing a business case, developing customer insights, delivering measurable ROI, collaborating across functions, building relationships with customers, differentiating the value of their brands — we discovered that in only half of all firms is there a belief that the CMO is effective. In 20 percent of all firms, they are considered totally ineffective. What’s worse is that the central metric of ROI is the area in which marketing is considered least effective.

It’s a strong indictment of the CMO. What’s worse is that CEOs must feel that incompetence breeds incompetence because it not only applies at the strategic level of the CMO but it applies to everyone the CMO is supposed to lead. When we look at the actual tactical decisions that marketers are supposed to make — finding new customers, increasing the marketing effectiveness of marketing investments, retaining existing customers, tracking customer value — fewer than half of all firms consider their marketing departments to be doing these at an effective level.

When we look at what explains this situation, the major obstacles in a third or more companies are things like lack of C-level support, lack of relevant skills in marketing executives, underinvestment in supporting technology, underinvestment in talent acquisition, training and retention, a disconnect over what marketing should be delivering, and a misalignment of the whole C-suite conception of marketing not being a strategic function.

No wonder we find that most CMOs feel unprepared for the major trending areas in marketing. They don’t feel they can handle the analytics that come from data explosion. They don’t know how to use social media properly. They don’t know how to deal with changes in channel behaviour or shifts in customer demographics. And why would they? Why would a CEO give resources to help CMOs get prepared when CMOs cannot marshal support for the importance of what they do, or even demonstrate that they have the competence to use those resources?

undefined Marketing is not the only functional area that’s had to deal with change. What have other areas done over that same 30-year period? Some innovations were a lot bigger in their impact on the practice of business than others. Some examples: total quality management, reengineering, lean manufacturing, balanced scorecards. What has marketing brought to the party in that same 30-year period? Nothing. Our response to change has been tactical. Instead of trying to find better things to do, we simply try to do the old things a little better.

undefined Marketing is not the only functional area that’s had to deal with change. What have other areas done over that same 30-year period? Some innovations were a lot bigger in their impact on the practice of business than others. Some examples: total quality management, reengineering, lean manufacturing, balanced scorecards. What has marketing brought to the party in that same 30-year period? Nothing. Our response to change has been tactical. Instead of trying to find better things to do, we simply try to do the old things a little better.

At some point, you need to realize that more of the same is not going to work, and that you have to find something better to do. I don’t have an answer to what this is, but let me start the dialogue by returning to square one and asking: Why do marketing at all? What do we really think marketing should try to achieve?

If we go back to that Economist survey of 2012 and ask that question of CEOs, this is what they say: driving revenue growth, finding new customers, improving reputation, creating new products and services, entering new markets, and retaining existing customers. The big one here, by a long shot, is driving revenue growth. But virtually every other one of these roles has as its implicit target increased top-line revenue; it is a volume game.

Every organization needs volume. The problem is that when you’re competing for resources — time, money, attention, and people — against other functional areas, you have to ask: If volume is my game, how will I stack up as a priority against other functional areas?

If you’re pursuing volume, how significant are you relative to, say, logistics or supply chain management? You’re going to ask for resources to try and build volume, they’re going to ask for resources to try and reduce costs. They are 2.4 times more impactful on profitability than you are. What makes it even worse is that when I do an initiative to reduce cost, the outcome is virtually 100 percent guaranteed. Lay off two people making $100,000 a year and it’s guaranteed that you will reduce your cost by $200,000. Give me $200,000 for an ad campaign? Trust me, it’ll work, it’ll be profitable.

The conflict isn’t just between marketing and other functional areas but within the marketing area as well. Product management, field sales, and customer service, three aspects of marketing that are supposed to work hand in glove, have fundamentally different goals and responsibilities, time horizons, and reasons for those time horizons. They have fundamentally different key performance criteria. Even when it comes to the latest messiah concept, big data or predictive analytics, their data priorities differ as well. How much luck do you need in order to develop an integrated plan?

The good news is that marketing has always had a transformational concept. Go back to the beginning of true marketing in its contemporary sense, brand management — that was our transformational model. The problem is that over time brand management has drifted from strategic to tactical. Brand management has become more focused on marketing communications, whether it is advertising, PR, or social media. We are more focused on breaking through the clutter and standing out from the crowd, with sexy and out-there ads and point-of-purchase displays, than with fundamental issues like who we should sell to, what we should sell them, and how we should promote it.

We forgot about the inside marketing job, of marketing to other functional areas in order to get them onside and to integrate with us. We forgot that the ultimate accountability has to rest on profitability, not sales or share. And we need to return to fundamental actions that marketers do that no one else can do, starting with segmentation.

Marketers, over the last 30 years, have let segmentation become a tool for choosing media: what kind of person reads this magazine, watches that program, or sees this billboard. Who really cares if they’re not the right customers to see the message in the first place? Nowadays, we have new technology that will let us become more intimate with customer behaviours than ever before. Whereas at one time we could only hypothesize the pathway to purchase, we can now actually follow the consumer in the act of shopping, but we’re not doing it.

We hear so much about whether marketing is an art or a science. It is some of both. But, more important, it is a discipline of identifying customers for whom you offer a credible message of superior value versus customers who can be fooled into buying your product. You may make that incremental sale but you won’t be able to hold onto it over the long haul. We have to get away from selling grand identities to selling grand competencies, away from focusing on awareness that brands exist, to concentrating on what those brands stand for, what they are associated with.

If we can start a dialogue around a new form of brand management, then instead of doing the wrong things really well, we will be focusing instead on identifying better things to do. And if we can execute those better things, we’ll execute the margin-sucking maggots in the process.