Commerce Society Launches The Queen’s Business Review

Who would have thought that tech-savvy Commerce students would choose to publish in print rather than online? The Queen’s Business Review (QBR), published by the Commerce Society, debuted in print and online in February. Its articles were contributed by first- to fourth-year Commerce students, with original illustrations supplied by Queen’s Fine Arts students.

It began as an online blog called “Day on Bay” — a web platform launched in 2011 for Commerce students to express their opinions on industry trends and the financial markets. When page views decreased and the site began to lose momentum, the editorial team, led by David Kong, BCom’14, decided an overhaul was required. A rebranding exercise led to the addition of a print publication, and The Queen’s Business Review began to take shape. “We thought that writers would devote more time and effort to a print publication in view of its lasting impact,” David explains. “We also believed that distributing print copies would increase our readership numbers.”

Once funding was approved, the self-taught editors mastered page-design software, finalized the content, and lined up illustrators and a printer. The magazine was hand-delivered to all Commerce students and made available throughout Goodes Hall. Advertisers, such as Shell Canada, came on board, and more are being sought to help offset the costs of producing two issues per school year.

The inaugural issue featured a wide range of topics — from global market predictions, to its cover story ‘IPOs as a Monopoly’. The second issue, published in April, tackled equally challenging topics: corporate tax avoidance, economic sanctions and Canada’s “dead-end” response to the Crimean crisis, and strategic challenges facing Tim Hortons as it expands internationally. It’s evident that the student authors have been inspired to dig deeper into subjects that have piqued their curiosity.

For a taste of what The Queen’s Business Review has to offer, check out the following article “Is My Social Network Worth $180,000”, by 2014/15 Editor-in-Chief Tom Kewley, Comm’15, which appeared in the February issue.

Is My Social Network Worth $180,000?

The democratization of sharing media online inspired the creation of “cultural value,” which subsequently increases the valuation of socially driven start-ups.

TOM KEWLEY

In the past two years, Facebook has made two significant acquisition offers. The first was to Instagram, for $1 billion in cash and stock options. It was accepted, and closed as a $715 million transaction in 2012. The second was to Snapchat, for $3 billion. That offer was rejected in 2013. Both of these offers are immense sums of money, especially as each target possessed zero dollars in revenue. It is at times like these, with infinite valuation multiples for fledgling tech companies, when market commentators say venture capitalists are not smart investors, valuations are frothy, and the world has gone crazy. Real, revenue-generating businesses are struggling, while those without clear business models are thriving.

Modern culture, which can be loosely defined as including art, communication, and interrelation between people, has increasingly featured technology as the middle-man for its dissemination. If one considers the role that Instagram plays in photography, and that Snapchat plays in communication – with millions of users, and even more millions of interactions between those users – then it is clear that within the depths of the ‘social graph’ there is financial value. Therefore, it is conceivable that holding a slice of market share within this industry of culture will give certain companies an intangible component to their valuations: cultural value. Famous artists transform human emotion and the world around them into art using a paintbrush on canvas. Now, the digital democratization of sharing media online has spurred the creation of a new “cultural value” that contributes to the valuation of certain hot technology companies such as Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat.

Modern culture, which can be loosely defined as including art, communication, and interrelation between people, has increasingly featured technology as the middle-man for its dissemination. If one considers the role that Instagram plays in photography, and that Snapchat plays in communication – with millions of users, and even more millions of interactions between those users – then it is clear that within the depths of the ‘social graph’ there is financial value. Therefore, it is conceivable that holding a slice of market share within this industry of culture will give certain companies an intangible component to their valuations: cultural value. Famous artists transform human emotion and the world around them into art using a paintbrush on canvas. Now, the digital democratization of sharing media online has spurred the creation of a new “cultural value” that contributes to the valuation of certain hot technology companies such as Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat.

Instagram transforms people’s ho-hum smartphone photos into beautiful, sharable snapshots of their lives through the careful application of one of 19 digital filters. According to Robin Kelsey, a professor of photography at Harvard, what we are seeing in the market today is “a watershed time when we are moving away from photography as a way of recording and storing a past moment, [and we are] turning photography into a communication medium.”

Instagram has done an incredible job of “democratizing” the field of photography so that amateurs can compete on photo quality with professionals using a few taps of their fingers. Instagram now has over 150 million active users on its platform, threatening the social networking giant Facebook with its rapidly increasing mindshare among the coveted teenage and early-20s demographic. From Facebook’s perspective, the risk of a loss of users and diminishing engagement on its own platform are two factors that would equally terrify the advertisers that support Facebook’s $140 billion market capitalization. Therefore, there is immense value in investing in fledgling companies that provide value outside of what larger firms are able to develop internally. Buying a product that organically develops a loyal user base, where those users spent a great deal of time, is a natural move for Facebook, which wants to attract more impressions for its advertisers. It is common to see fairly intense bidding in M&A processes like this, for many firms can see the obvious competitive value of building a defensive moat around their core consumer product. Instagram is an excellent example of strategic value meeting and creating cultural value.

Snapchat

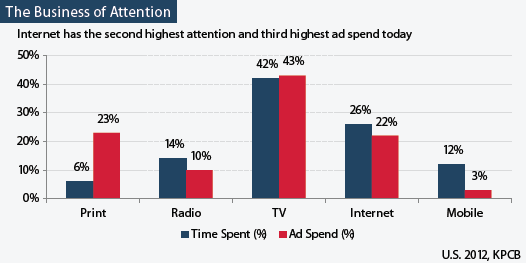

Not to be outdone, another popular social communication app, Snapchat, similarly allows people to instantly share microcosms of their lives in the form of self-destructing photos. Like Robin Kelsey’s analysis, well-respected tech commentator, Gary Vaynerchuk, recently wrote an article titled “You See Snapchat as Sexting and a Fad. I See the Future.” His thesis argues that all companies are in the business of attention, and, in a world where microseconds are prized by consumers and advertisers alike, forcing consumption of content for 3-10 seconds is a very unique and addictive restriction.

Vaynerchuk’s piece earned attention in the tech community and a response from PandoDaily’s Ryan Hoover. Hoover further develops the thesis, arguing that Snapchat, in a similar vein as Instagram, has created habitual engagement. According to Hoover, Snapchat has done this a few ways: through friction-free creation, lowered inhibitions, one-to-one ‘hyper-personal’ communication at scale, read receipts, and feeding individual curiosity.

Snapchat’s user base sends 350 million photo messages per day. Its 23-year old CEO, Evan Spiegel, raised $60 million in capital for his 17-person company at a jaw-dropping $860 million valuation in June 2013. Snapchat’s rapid ascent into such a dominant position in the instant messaging space has caught many, including venture capitalists, off guard. The same question has to be asked – how is this company worth $860 million if it is not making any money? Facebook, again, is terrified by the prospect of lost users and lost advertising dollars. In response, it tried to make a Snapchat clone, Poke, which failed. On October 25, 2013, Snapchat announced its intention to raise more venture capital at a $3.5 billion valuation. That same day, rumors surfaced that Spiegel reportedly rejected the advances of Zuckerberg and another $1 billion offer. Facebook’s Instagram has even developed a competitive product, Instagram Direct, which seeks to capture users’ attention with hyper-personal messaging. Again, this strategic value, coupled with the inherent (and defensible) social and behavioural value that Snapchat has created, gives the company significant cultural value.

Start-ups Bridging the Death Valley Curve

In the early days of a socially-based tech start-up, making money is the wrong goal. To a point, user metrics are superior indicators. In a blog post titled, “How will they make money?” reputed Silicon Valley venture capitalist Josh Elman of Greylock Partners, says, “There is a reason that the first five slides of Facebook’s quarterly earnings reports are exclusively dedicated to reporting user numbers.” With Facebook’s market capitalization now exceeding $140 billion, the question posed by Elman was one that plagued the company for the first era of its existence. In the social realm, the path to monetization of a user base is dangerous. Go too far, and you risk alienating your user base. Fail to go far enough, and report one too many ‘revenue-free quarters,’ and you will eventually go bankrupt unless supported by a third-party investor. This time period, referred to as the ‘death valley curve,’ is essentially the time post-financing, pre-revenue. Overflow this territory with high-valuation companies, and you have speculative risk being absorbed by venture capital firms, and headlines in major news publications speaking of an impending bubble. Snapchat remains in this territory. Instagram escaped it by being acquired.

Implications for the Individual

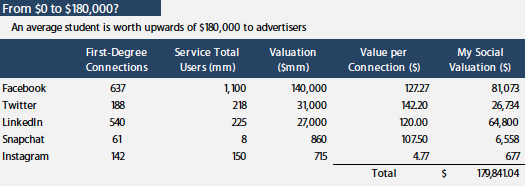

If the trends of the population have a value, then the individual’s social networks must also have a role in the conversation. In 2003, Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat did not exist. Neither did other major players in the social realm, such as LinkedIn or Twitter. Today, average teenagers have social networks and online ‘brands’ worth 6-figures to advertisers and other tech companies.

With this in mind, it is no wonder that a sense of narcissism develops around the individual’s creation and curation of his or her ‘art’. This is the ‘industry of culture’, the ‘business of attention’. Nathan Jurgenson, in a recent piece for The Atlantic, took the whole idea of fueling a narcissistic feedback loop one step further. He proposes that people – especially young people – are in danger of developing a ‘Facebook Eye’, with “moments of everyday life increasingly informed by thoughts of what might best translate into a Facebook post that will draw the most comments and likes.” Jurgenson is not the first to assert that “Facebook’s most valuable asset is not simply its millions of users, but the millions who are constantly updating their likes and dislikes, their friends and acquaintances – and, increasingly, their daily behaviour down to the minute.” This is a daunting proposition. But it is also why social applications that gain mass following will always hold value. Get too much attention from a loyal user base and you will get acquired (Instagram), or get massive rounds of venture financing (Snapchat), or file for your own public offering (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter).

Valuing a low-revenue startup is difficult. Investors are simply trying to place a bet that there will be logical path to ‘exit’ so they are able to return dividends to themselves or their limited partners. Applications that change the fundamental psychology and sociology of human communication must be worth something. Relying on predictions and unscientific intuition, there’s no telling whether that statement will be accurate over the long-term, or whether we are currently seeing the second great bubble of the consumer technology industry.