Team Canzania Can Climb Mountains

EMBA'05's Global Business Project Continues Economic Development Projects In Tanzania Long After Class Dismissed

Six Queen’s MBAs. Two-thousand dollars. One intrepid doctor. Several dozen enterprising villagers. And a whole lot of bees. That’s what it took to jumpstart the economy of Matapwili, a remote village in Tanzania.

The team tackles Mount Kilimanjaro.It all began with those six MBAs: Gurjit Gill, Deirdre Fitzpatrick, Ben La Pianta, Richard Provan, Dan Price, and Edye St. Hill. As part of their Global Business Project during their 2005 Executive MBA, the team was tasked with implementing a business opportunity outside of North America.

The team tackles Mount Kilimanjaro.It all began with those six MBAs: Gurjit Gill, Deirdre Fitzpatrick, Ben La Pianta, Richard Provan, Dan Price, and Edye St. Hill. As part of their Global Business Project during their 2005 Executive MBA, the team was tasked with implementing a business opportunity outside of North America.

The team knew they wanted to “give back” by focusing on the non-profit sector. Their goal was to identify a project that empowered a local community, developed its economy, and was both sustainable and eco-friendly. They also wanted something “do-able.” Deirdre remembers well a fitting quotation of Prof. Julian Barling’s that the team took to heart: “It’s the little things that make a big difference in the long run.”

At the time, Deirdre was working for Barrick Gold, which had just begun mining operations in East Africa. Through contacts at the company, she located staff doctor Rob Barbour, who runs an eco-lodge called Camp Kisampa with his wife, Jackie. Dr Rob – as he’s known to the locals – identified at least 30 development projects the team could tackle in nearby Matapwili. Edye and the others immediately jumped at the chance to work on economic development in Africa. “I’d been reading that we could eliminate poverty by the year 2025,” says Edye, “so when Deirdre sent the note about working in Tanzania, there was no question that I was in.”

Before leaving for Africa, the team narrowed down the possibilities and did extensive research on potential projects, including beekeeping, fish farming, and building a high school. They also collected pledges from family and friends in support of a planned hike up Mount Kilimanjaro, with the proceeds supporting whichever development project they ultimately settled on.

Before leaving for Africa, the team narrowed down the possibilities and did extensive research on potential projects, including beekeeping, fish farming, and building a high school. They also collected pledges from family and friends in support of a planned hike up Mount Kilimanjaro, with the proceeds supporting whichever development project they ultimately settled on.

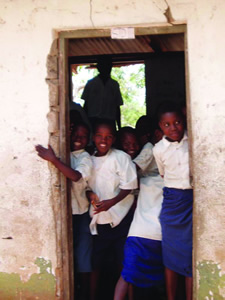

Their fundraising objectives achieved, the team flew to Tanzania in September 2004. They slept in open-air tents near a savannah that is home to night-prowling leopards, beside a river filled with hippos not afraid to overturn boats, and crocodiles known to attack humans. After meeting the villagers and playing with the children, they got right down to business.

From Bee Keeping To Fish Farming To A School, These EMBA Grads Are Making A Difference In A Small Village In Africa

The team decided on two projects, one helping Dr. Rob create a marketing plan for Camp Kisampa, the other designed specifically to improve conditions in Matapwili. They spent many hours with the village council discussing which of the potential projects they’d researched would work best in Matapwili. “The key to successful economic development is to get buy-in from the constituents,” Deirdre explains. Eventually and after much discussion, everyone agreed that the beekeeping project was the best fit. “It was a workable chunk with a real result at the end,” she says.

Meeting with Team Canzania at Kisampa, seated from left Gurjit Gill, Dr. Rob Barbour, Richard Provan, Deirdre Fitzpatrick, Dan Price (standing), Ben La Pianta, and Edye St. Hill.Give a man a fish, he eats for a day. Teach a man to fish, he eats for a lifetime. This famous Chinese proverb could have been the project’s mission statement. “Sustainability was key,” says Edye. “We didn’t want to just hand out money.” Accordingly, the team proposed investing the money raised to establish a revolving loan. The first $2,000 loan would be given to the inaugural beekeepers to pay Honey Care Africa, an organization that specializes in providing equipment and training to local beekeepers, run, perhaps not incidentally, by Queen’s alumnus Farouk Jiwa, BSc’98. Those villagers in turn would harvest a crop and receive half the honey’s value in cash. The other half of the proceeds would replenish the revolving loan to fund other villagers in the future who might want to take up beekeeping, and so the cycle would continue. Upon repayment of their loans, the individual beekeepers would be able to retain all future profits. Dr. Rob would assist by finding buyers for the honey and administering the finances.

Meeting with Team Canzania at Kisampa, seated from left Gurjit Gill, Dr. Rob Barbour, Richard Provan, Deirdre Fitzpatrick, Dan Price (standing), Ben La Pianta, and Edye St. Hill.Give a man a fish, he eats for a day. Teach a man to fish, he eats for a lifetime. This famous Chinese proverb could have been the project’s mission statement. “Sustainability was key,” says Edye. “We didn’t want to just hand out money.” Accordingly, the team proposed investing the money raised to establish a revolving loan. The first $2,000 loan would be given to the inaugural beekeepers to pay Honey Care Africa, an organization that specializes in providing equipment and training to local beekeepers, run, perhaps not incidentally, by Queen’s alumnus Farouk Jiwa, BSc’98. Those villagers in turn would harvest a crop and receive half the honey’s value in cash. The other half of the proceeds would replenish the revolving loan to fund other villagers in the future who might want to take up beekeeping, and so the cycle would continue. Upon repayment of their loans, the individual beekeepers would be able to retain all future profits. Dr. Rob would assist by finding buyers for the honey and administering the finances.

“Sustainability Was Key,” Says Edye.“We didn't Want To Just Hand Out Money.”

After their hike up Mount Kilimanjaro, the team returned to Canada to complete their two projects. They worked on their team assignment, which was reviewed by and discussed with their project advisor, Ken Petersen, EMBA’00, finally submitting their completed paper at the end of the program to Prof. Roger Wright. They also finished collecting their pledges and wired the money to Dr. Rob to get the beekeeping project off the ground.

Beekeeper at work. With diplomas in hand, the team was set to disband. Mission accomplished, after all. A nice little honey business in a small village in Tanzania could have been their legacy. But visions of Matapwili persisted. “There was no way you could meet these people without it changing your life,” says Deirdre. “They became a part of us.” Edye agrees, relating how, about a year after returning, she had a dream about Hashim (pictured on the cover) a villager she’d met who suffers from the disfiguring condition elephantiasis and who aspired to start a small embroidery business. “I knew I had to keep helping,” she says. And so Team Canzania (Canada + Tanzania) was officially born, with a mission to assist Matapwili for as long as possible.

Beekeeper at work. With diplomas in hand, the team was set to disband. Mission accomplished, after all. A nice little honey business in a small village in Tanzania could have been their legacy. But visions of Matapwili persisted. “There was no way you could meet these people without it changing your life,” says Deirdre. “They became a part of us.” Edye agrees, relating how, about a year after returning, she had a dream about Hashim (pictured on the cover) a villager she’d met who suffers from the disfiguring condition elephantiasis and who aspired to start a small embroidery business. “I knew I had to keep helping,” she says. And so Team Canzania (Canada + Tanzania) was officially born, with a mission to assist Matapwili for as long as possible.

Edye donated the $1,200 needed for a sewing machine for Hashim, though finding a non-electric one in Tanzania wasn’t easy. Hashim’s self-taught embroidery work has been characterized as “stunning, very colourful, and very well done.” He also has begun sewing uniforms, tents, and linens, serving as a positive example for the entire community, and now another interested villager should be receiving her own sewing machine very soon.

The team’s focus then shifted to another project the village council had proposed: building a local high school. Young people were leaving the area in droves, the councillors reported, with few prospects for jobs or secondary education, and their parents wanted them to stay. “Just $5,000 would build an entire school, including construction material, local labour, furniture, textbooks, and school supplies,” Deirdre explains. Inspired by being able to do so much for so little, Team Canzania decided to mark their MBA graduation with a fundraising party in the Toronto Beaches. Their target met, the funds were transferred to Matapwili and the school opened in the spring of 2007.

The team’s focus then shifted to another project the village council had proposed: building a local high school. Young people were leaving the area in droves, the councillors reported, with few prospects for jobs or secondary education, and their parents wanted them to stay. “Just $5,000 would build an entire school, including construction material, local labour, furniture, textbooks, and school supplies,” Deirdre explains. Inspired by being able to do so much for so little, Team Canzania decided to mark their MBA graduation with a fundraising party in the Toronto Beaches. Their target met, the funds were transferred to Matapwili and the school opened in the spring of 2007.

Again, the group could have stopped there, with three successful ventures to their credit. But, feeling the momentum, they turned their attention to a fish farming enterprise to provide a viable source of protein to the villagers’ diet while exploring the commercial market potential. Like beekeeping, fish farming is a sustainable and eco-friendly enterprise, says Edye, who explains that the environmental problems and diseases associated with fish farming in the West are not issues in Tanzania. The project is not without risk, though, since the fish are located in the aforementioned hippo- and crocodile-infested river. For about $2,500 invested in a revolving loan, consultants provide training and equipment, including how to preserve the fish so the catches last. Edye spearheaded a fundraiser to support this initiative by participating in a sailing challenge from the British Virgin Islands to Toronto. “If fish farming takes off in Matapwili,” she says, “I want to take it along the river to the other villages.”

“We've Had No Failures,” Says Deirdre, “But There's Still So Much To Do.”

Team Canzania’s initial beekeeping project has unquestionably taken off, yielding tangible results four years later. The mostly female beekeepers tend about 150 beehives that produce 500 to 600 kilograms of organic acacia honey a season, with a boutique delicatessen in Dar es Salaam providing a guaranteed market. Wax for furniture polish is another successful by-product, and the village is considering producing hives themselves as an offshoot industry. Another result, this one quite unexpected, has been felt in the social fabric of the village. In Muslim Matapwili, women traditionally have had no money and very little power. Since Team Canzania’s arrival, they have started sewing circles and craft projects, which in turn have further strengthened their own influence.

Team Canzania’s initial beekeeping project has unquestionably taken off, yielding tangible results four years later. The mostly female beekeepers tend about 150 beehives that produce 500 to 600 kilograms of organic acacia honey a season, with a boutique delicatessen in Dar es Salaam providing a guaranteed market. Wax for furniture polish is another successful by-product, and the village is considering producing hives themselves as an offshoot industry. Another result, this one quite unexpected, has been felt in the social fabric of the village. In Muslim Matapwili, women traditionally have had no money and very little power. Since Team Canzania’s arrival, they have started sewing circles and craft projects, which in turn have further strengthened their own influence.

“We’ve had no failures,” says Deirdre,“but there’s still so much to do. You can throw money at these problems, but that’s not sustainable or realistic. So we need to concentrate on these little wins. Anything is something.” What’s perhaps most heartening about these various projects, according to Team Canzania’s website, is that they have given people an opportunity “to create their own livelihoods, without dependence on government or NGOs. They instill pride and a sense of control over their future and the economic well-being of their children and their community at large.”

“There Was No Way You Could Meet These People (In Matapwili) Without It Changing Your Life,” Says Deirdre.

In addition to continuing to help Matapwili, Team Canzania plans to concentrate on the nearby village of Mkwaja, with fundraisers already planned throughout the year, several themed around African foods and wines and generously supported by friends and colleagues. One immediate goal is to create a sustainable education fund. Initially, it will support one student who is in the process of obtaining a Wildlife Management Diploma. When he repays his loan, whenever it doesn’t present a financial burden to do so, the money will then go on to finance another student. In addition, the team would like to see the student spend time mentoring in the village and eventually choosing the next recipient. On a related note, the children of team member Ben La Pianta are helping two high school students with their fees, at a cost of $200 per student per year.

In addition to continuing to help Matapwili, Team Canzania plans to concentrate on the nearby village of Mkwaja, with fundraisers already planned throughout the year, several themed around African foods and wines and generously supported by friends and colleagues. One immediate goal is to create a sustainable education fund. Initially, it will support one student who is in the process of obtaining a Wildlife Management Diploma. When he repays his loan, whenever it doesn’t present a financial burden to do so, the money will then go on to finance another student. In addition, the team would like to see the student spend time mentoring in the village and eventually choosing the next recipient. On a related note, the children of team member Ben La Pianta are helping two high school students with their fees, at a cost of $200 per student per year.

The results for the members of Team Canzania themselves have been profound. “We were left totally transformed,” says Deirdre.“I went to Matapwili, but I didn’t feel troubled,” says Edye. “Instead, my whole focus changed. I had connected with these people and knew I could help them in a very concrete way.”

The goal is to keep Team Canzania going for as long as possible.“This is more than just about raising money,” says Edye. “It’s about raising awareness.” Deirdre adds: “I want to bring my kids there and get them involved. This is meant to be long-term and sustainable, one village at a time.”

Ottawa and Nairobi hospitals twinned, thanks to EMBA’05 Ottawa Team

While the Toronto-based EMBA’05s destined to become Team Canzania were working on their Global Business Project (GBP), a like-minded group of Ottawa EMBA’05 students decided independently to also focus their project on the non-profit sector in a developing country.

While the Toronto-based EMBA’05s destined to become Team Canzania were working on their Global Business Project (GBP), a like-minded group of Ottawa EMBA’05 students decided independently to also focus their project on the non-profit sector in a developing country.

It started with Dr. Karim Damji, EMBA’05, an ophthalmologist with The Ottawa Hospital (TOH), who saw an opportunity to use the GBP to accelerate a twinning project he’d already been working on with TOH’s Chief of Staff, Dr. Chris Carruthers. Hospital twinning enables like-minded institutions in the developed and developing world to exchange knowledge, skills, and services and facilitate ongoing professional development.

Seeing the value of having ‘free’ consultants work on the project, Chris supported the proposal to have an EMBA team develop a framework for identifying a twinning partner. Karim approached his teammates, Randy Elias and Wendy McCallum, for help. Inspired by Karim’s vision of making a contribution in the non-profit sector, particularly in healthcare, Randy and Wendy eagerly signed on.

Ottawa EMBA’05 team in front of Aga Khan University Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. From left, Randy Elias, Dr. Karim Damji, and Wendy McCallum. The team immediately set to work with Chris to build a rationale for twinning and to produce a methodology for choosing a partner within the GBP timeline. “It’s fine to have ideas,” says Karim, “but you need to structure those ideas in a thoughtful manner, one that lends itself to execution and follow-through.” After investigating best practices from other hospitals that had successfully twinned, the team created selection criteria based on such factors as political stability, existing healthcare systems, the presence of internal champions, mutually acceptable goals, commitment to invest human and other resources, and ability to measure outcomes.

Ottawa EMBA’05 team in front of Aga Khan University Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. From left, Randy Elias, Dr. Karim Damji, and Wendy McCallum. The team immediately set to work with Chris to build a rationale for twinning and to produce a methodology for choosing a partner within the GBP timeline. “It’s fine to have ideas,” says Karim, “but you need to structure those ideas in a thoughtful manner, one that lends itself to execution and follow-through.” After investigating best practices from other hospitals that had successfully twinned, the team created selection criteria based on such factors as political stability, existing healthcare systems, the presence of internal champions, mutually acceptable goals, commitment to invest human and other resources, and ability to measure outcomes.

In putting together a list of potential partners, the team researched hospitals in Asia, South America and Africa, but focused on Africa, especially after receiving a request from Stephen Lewis, the former UN Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS, to consider the Queen Elizabeth II Hospital (QEH) in Lesotho. It became one of their short-list candidates, along with the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH-N) in Nairobi, Kenya.

The team gets a tour of the hospital in Nairobi.With their preliminary research complete, there were still important unknowns to investigate, and so Karim, Randy, Wendy, and Chris went to Africa in the spring of 2005. The first stop was Nairobi and the AKUH-N, with its impressive facilities. “The AKUH-N was transitioning to becoming a teaching hospital,” says Wendy, “and they have a passionate leadership.”

The team gets a tour of the hospital in Nairobi.With their preliminary research complete, there were still important unknowns to investigate, and so Karim, Randy, Wendy, and Chris went to Africa in the spring of 2005. The first stop was Nairobi and the AKUH-N, with its impressive facilities. “The AKUH-N was transitioning to becoming a teaching hospital,” says Wendy, “and they have a passionate leadership.”

The group then headed to Lesotho, where they found quite a different situation: a hospital challenged by a lack of resources and poor infrastructure. They learned that the AIDS crisis was having a devastating effect on the country, impacting the availability of trained hospital staff to manage the crisis. The capital city was filled with people working hard to address this human catastrophe: UNICEF workers, volunteers from the Clinton Foundation’s HIV/AIDS Initiative, and World Health Organization representatives. Doctors sent by the Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) to teach instead started practising frontline medicine.

On a nine-hour layover in Amsterdam on their return trip, the team took out their laptops at an airport café and worked on their report, recommending that the Ottawa Hospital twin with its counterpart in Nairobi. “The AKUH-N had the human and financial resources to put into such a project,” says Karim, “and they aspire to become a hub of regional excellence with international standards.” While the need at QEH was obviously enormous, the twinning initiative could not support the level of aid needed so urgently, and the OHA was already intervening there, providing life-saving antiretroviral therapy. Upon their return to Ottawa, the team handed in their GBP report to project supervisor Dr. Douglas Tessier. They also submitted it to The Ottawa Hospital’s board, which subsequently supported twinning in principal with TOH’s Nairobi counterpart.

On a nine-hour layover in Amsterdam on their return trip, the team took out their laptops at an airport café and worked on their report, recommending that the Ottawa Hospital twin with its counterpart in Nairobi. “The AKUH-N had the human and financial resources to put into such a project,” says Karim, “and they aspire to become a hub of regional excellence with international standards.” While the need at QEH was obviously enormous, the twinning initiative could not support the level of aid needed so urgently, and the OHA was already intervening there, providing life-saving antiretroviral therapy. Upon their return to Ottawa, the team handed in their GBP report to project supervisor Dr. Douglas Tessier. They also submitted it to The Ottawa Hospital’s board, which subsequently supported twinning in principal with TOH’s Nairobi counterpart.

The project has been up and running for the past three years, with TOH endorsing informal relationships on an interdepartmental basis. Doctors Damji and Carruthers have since travelled to Kenya several times to forge partnerships between the two facilities’ ophthalmology and orthopaedic groups. They piloted a ‘Sandwich’ Fellowship queensbusiness.ca SUMMER 2008 MAGAZINE 19 model, in which African specialists rotate learning segments between AKUH-N and TOH.

Wendy, Chris, Karim and Randy on safari.“The first glaucoma subspecialist in Kenya, and likely in all of sub-Saharan Africa, is about to return to Nairobi,” Karim says proudly, and an orthopaedic candidate who trained at TOH returned to Nairobi in late May. Fortunately, recent political events in Kenya have not had any long-term negative effects on the partnership.

Wendy, Chris, Karim and Randy on safari.“The first glaucoma subspecialist in Kenya, and likely in all of sub-Saharan Africa, is about to return to Nairobi,” Karim says proudly, and an orthopaedic candidate who trained at TOH returned to Nairobi in late May. Fortunately, recent political events in Kenya have not had any long-term negative effects on the partnership.

The Global Business Project has had a lasting impact on the team members. “We encourage other EMBA teams to focus on the non-profit sector,” says Wendy. “It was such a fulfilling and worthwhile thing to do.” Karim agrees: “I wanted to improve people’s health-related quality of life. Our goal was to help people help themselves. And we’ve definitely started to achieve that.”

- 1 of 2

- ›