Comrade Pazderka

Bo Pazderka landed at Ottawa’s airport after a flight from Rome in September 1968, with only $20 and two small suitcases to his name. He knew no one in the city, or in all of Canada, for that matter. Looking around for signs of a bus that might take him to a youth hostel, he spotted an older couple holding a sign that read “Pazderka”. It turned out he had friends in this faraway place after all.

Mr. and Mrs. Krupka who had defected in the 1950s, were members of a Czech association. Like many of their compatriots, they had closely followed news of the invasion of their homeland by 500,000 Soviet and Warsaw Pact troops a few weeks earlier. This was the Soviet response to the Prague Spring, a period of attempted reforms to democratize Czechoslovakia and loosen it from Soviet control.

The Canadian consulate in Rome had alerted the association to Bo’s arrival, a standard practice that helped many of the 12,000 Czechs who fled to Canada in the invasion’s aftermath. The consulate had also covered the cost of his airfare, a loan that Bo repaid within a year.

The couple took Bo in, and within ten days had helped him land a job as a research assistant to the Royal Commission on Farm Machinery. Having grown up on a farm in a small Czech village, Bo was certainly familiar with the subject. “As a kid I used to cut the grass with a scythe, though I didn’t share this with my colleagues,” he recalls.

Being circumspect was a necessity for those living under Czechoslovakia’s Communist regime in the post-WWII years. A member of Bo’s family had learned this lesson all too well. His father’s cousin spent 11 years in a Czech prison for the crime of having witnessed several friends escape across the border, one of whom shot and killed a border guard.

Bo’s earliest memory of the Soviet presence was less harrowing but still vivid 72 years later. “Near the end of the war, when I was three-and-a-half, I remember hiding in a candle-lit wine cellar with my parents, sister and grandparents,” he recalls. “We could hear the sounds of the battle between the Germans and Red Army above us. When the Soviets arrived, they requisitioned one of our pigs and I can still remember how the pig squealed as it was led away. One of the soldiers ordered my mother to make goulash. He put me on his knee and commanded, ‘Eat!’ Maybe he was a father of a young son, or perhaps he was testing my mother to ensure she hadn’t poisoned the food.”

Liberation by the Red Army eventually led Czechoslovakia to become one of the satellites of the USSR. Bo took his place in the local school and excelled at his studies. He passed his university entrance exams and was accepted at the School of Economics in Bratislava. University tuition was covered by the state, as Bo and his classmates were reminded all too often.

“You had to keep up your marks or you’d be kicked out,” says Bo of a punishing program from which only 80 of 160 freshman classmates graduated. However, a reprieve was possible. “A failing student would be told,

‘Well, Comrade, you obviously do not appreciate how much the working-class citizens of our country have contributed toward your education. Join their ranks as a manual labourer for one year and then you can reapply.’”

After graduating in 1964, Bo, like all young Czechs, faced two years of compulsory military service. He had joined an officer-training program in school that enabled him to shorten his obligation to one year. Basic training included trench-digging and target-shooting. (“I was a pretty good shot,” he recalls.) The worst was chemical-weapons training, a prerequisite during the Cold War era. “We had to wear hooded suits that made us sweat profusely, and the old oxygen masks made breathing extremely difficult.”

After completing his military service as a finance clerk at a base close to the German and Austrian borders, Bo was assigned his first job. “There was no choice involved,” Bo explains of the compulsory three-year contract position. “The attitude was,‘Your country paid for your education, Comrade, and you will go where your country needs you.’ Apparently my country needed me to work at the state bank in a town in the east. I explained I’d already found a job close to my home and was told, ‘No, Comrade, you will work in the bank in Košice.”

Two years into his contract, Bo landed a job at a finance-research institute in Bratislava, thanks to a former professor’s intercession on his behalf. He started there within a month of the accession of a new reform-minded government. Bo had thus far managed to avoid becoming a member of the Communist Party, the only avenue for success in business or in government. As reforms took hold, he wasn’t alone in hoping that this situation would change.

Instead, on the evening of August 20, 1968, Soviet tanks moved into Bratislava. “There were long line-ups outside of grocery stores, and tanks in the square close to my office,” Bo recalls. There were also many rumours, including a persistent one that university graduates would be sent to Siberia for ideological retraining. “I decided I wasn’t going to wait around to see if it was true,” Bo says wryly.

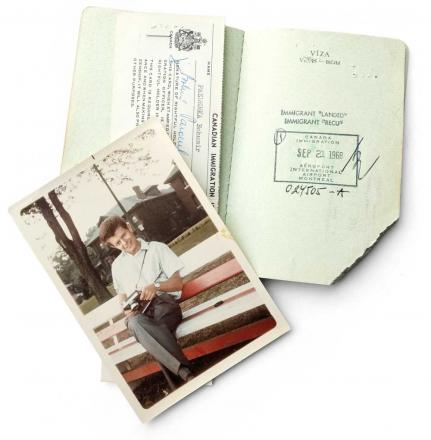

Photo of Bo sightseeing in Ottawa in the fall of 1968, shortly after his arrival and his cancelled passport from the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, complete with his Canadian immigration form.

As it turned out, 22 years would pass before he would see his homeland again, though he managed occasional visits with family members in Soviet satellite states. Had he returned to the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, he risked a two-year prison sentence for having defected.

Bo was fortunate that his family wasn’t subjected to any retribution for his unlawful departure. Had family members worked in government or business, they would most likely have lost their jobs. His boss at the research institute was fired as a result of the defections of Bo and a colleague. “To have two of twelve employees defect appeared to the authorities that our boss had suffered from ideological weakness,” Bo explains. “Fortunately, his job as a professor at the university wasn’t affected. The ramifications could have been even worse. I learned many years later that the institute’s secretary had been a member of the state secret police.”

The timing of the Soviet invasion turned out to be advantageous for Bo. The year before, he had befriended an Italian fellow who had suggested that Bo visit him. With a formal invitation in hand, Bo was able to get an exit visa for a three-week vacation. After a brief stay with the Italian friend in the south, Bo made his way to Rome in the hope of finding a country that would accept him. The choices were limited; only Sweden, Switzerland, Australia and Canada had opened their borders to émigrés without first requiring a stay in a refugee camp.

“Swedish wasn’t one of the five languages that I spoke; Switzerland had a reputation for being unwelcoming to refugees; Australia was too far; so that left Canada,” Bo explains. He was first interviewed by an RCMP officer. “He saw on my application that I spoke five languages, and said, ‘Five languages? You must be a spy!’ I managed to assure him that I was no such thing,” Bo says.

The next interview, with an immigration officer, was almost his undoing. “He asked my profession, and I replied ‘economist’, then he looked in a big book and said, ‘Good, we need economists.’ I don’t know what possessed me, but I blurted out, ‘But I was trained as a Marxist economist.’ The fellow consulted his book again and said, ‘It doesn’t say anything about that in the book,’ so I was approved.”

His Marxist education did turn out to be an impediment when Bo attempted to attain Canadian academic credentials. He decided to pursue a Master’s degree at Queen’s. “Rod Fraser, who was the head of graduate studies, asked me what I knew about Keynesian economics. I replied,

‘I was taught that Keynesian economics represented the last desperate attempt by the imperialists to save capitalism from its inevitable collapse.’

He suggested that I take some evening undergraduate economics courses to come up to speed, which I did, at the University of Ottawa.”

His PhD studies at Queen’s were a challenge. Before writing an assignment, often he would consult undergraduate textbooks to grasp the fundamentals before tackling complex subjects. He also needed some help with his English, which his British girlfriend, Julie Kilpatrick, later his wife, was happy to provide.

Bo joined Queen’s business school’s faculty in 1974, and has taught in the Commerce, MBA and PhD programs ever since. His 8,600 students (200/yr x 43 yrs, per Bo’s calculation) have benefitted from his unique perspective and engaging teaching style. His colleagues, consulting clients and the discipline of economics have also been enriched by his research input, a list of which takes up five single-spaced pages of his c.v. His local community has been improved through his service to hospital and charitable foundation boards too many to mention.

How fortunate we all have been that an immigration officer, deluged by thousands of fleeing Czechs, saw fit to stamp young Bohumir Pazderka’s landed-immigrant application “Approved”.